192: Momentum VS Perfection

The Biggest Question in Climate Right Now? (Part One)

About this episode

Welcome to another episode of Outrage + Optimism, where we examine issues at the forefront of the climate crisis, interview change-makers, and transform our anger into productive dialogue about building a sustainable future.

This week Tom Rivett-Carnac introduces the first of his two-part series on Momentum vs Perfection by looking at the different theories of change within the climate movement and asking if and how they can co-exist to drive the level of scale and action needed in this decisive decade.

He is joined on this complex and emotive journey by guest co-host Fiona McRaith, Manager of Engagement & Delivery and Special Assistant to the President & CEO at climate philanthropy fund Bezos Earth Fund. Fiona brings a (significantly younger) Gen Z perspective to this thought-provoking discussion.

Tom kicks off the episode by inviting Fiona and Outrage + Optimism listeners to imagine being given a great task: to change the world in some fundamental way. He asks: how would you approach the challenge?

Would you commit to taking the first step, believing this will create a second, then a third towards your goal, assuming you will not lose sight of your path or integrity in the noise and confusion of the world? Or, would you hold fast to your moral convictions and refuse to change your position regardless of the complexities you might face along the way, in line with moral leaders of the past?

Tom posits the two theories of change, referred to in this episode broadly as Momentum v Perfection, should be aligned, but increasingly appear to be in conflict. An important question we will be trying to answer throughout this series is: How do we move forward as a collective community?

Our co-hosts speak with a series of esteemed guests on this timely and important question, including:

-

Helen Pankhurst, Senior Advisor at international humanitarian agency CARE International, women’s rights activist, and the direct descendant of Emmeline Pankhurst and Sylvia Pankhurst, both leaders in the suffragette movement

-

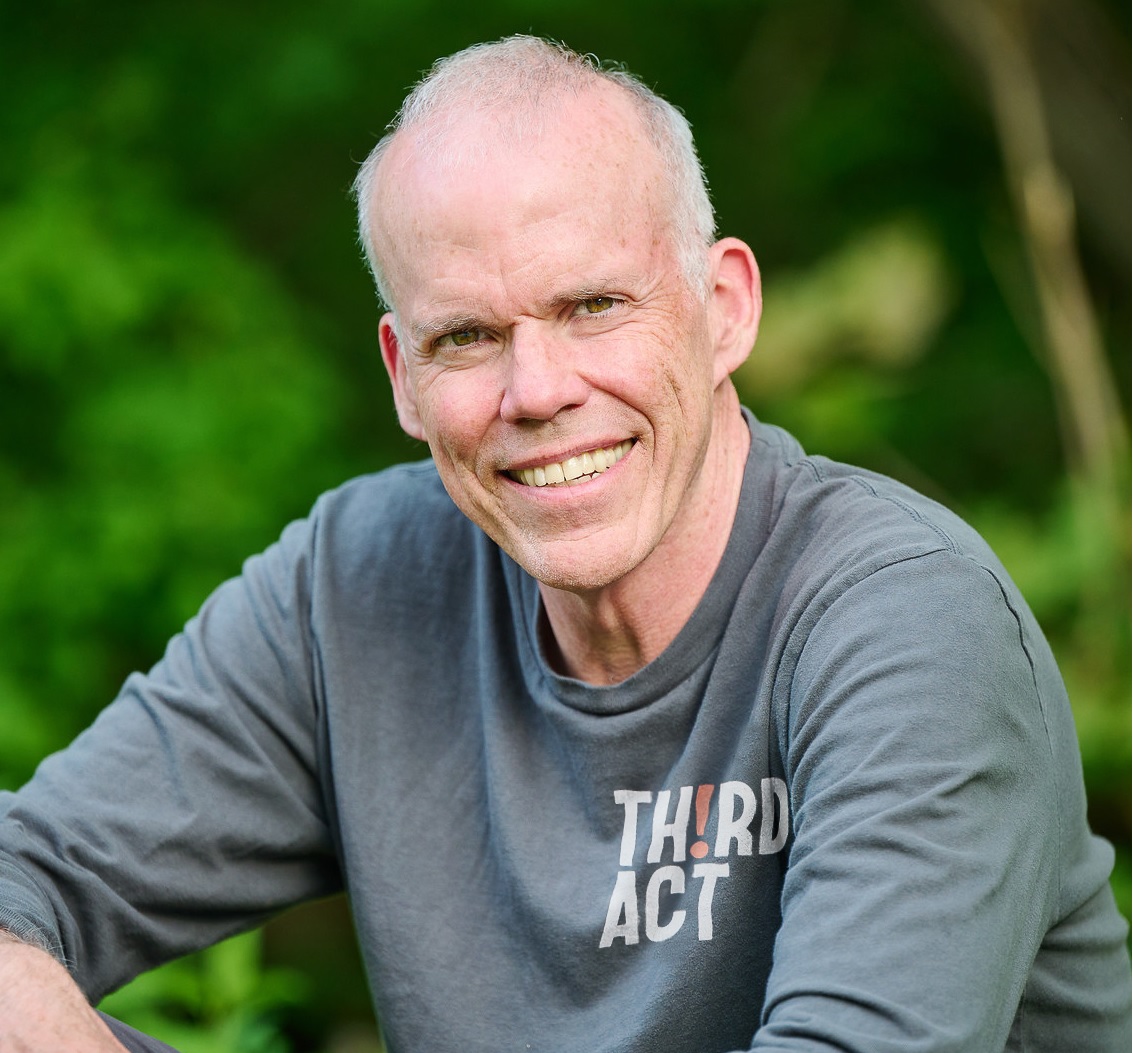

Bill McKibben Author, educator, environmentalist, Founder of Third Act and Co-Founder of international environmental organization 350.org

-

Environmental activist and Co-Founder of global environmental movement Extinction Rebellion, Gail Bradbrook

-

Jerome Foster II, Co-founder of Waic Up and youngest member of the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council

-

Director of mission-driven consulting firm Reos Partners, Adam Kahane

-

Previous Director of Strategy for the Cabinet Office for COP 26 (the United Nations’ annual climate conference) Charles (Charlie) Ogilvie

Don’t miss Part One of this incredible and timely conversation, including insights from previous movements, generational collaboration, the value of civil disobedience, the role of data and measurement, and whether agreement between sides is necessary for advancement.

And be sure to look out for the final episode of this mini-series next week, in which our co-hosts, with the help of their guests, will hopefully draw some conclusions to help guide us in these crucial years.

Please don’t forget to let us know what you think here, and / or by contacting us on our social media channels or via the website.

NOTES AND RESOURCES

Momentum vs. Perfection - Over To You

O+O Live Q&A: Join Us - April 19, 2023 @ 4.30pm BST / 11.30am EST

Register to join us for our live online Q&A episode of Outrage + Optimism and put your question to our hosts, please click on this link and follow the instructions.

To learn more about our planet’s climate emergency and how you can transform outrage into optimistic action subscribe to the podcast here.

Learn more about the Paris Agreement.

Fiona McRaith, Manager, Engagement & Delivery and Special Assistant to the President & CEO, Bezos Earth Fund

LinkedIn | Twitter | Instagram

Helen Pankhurst, women’s rights activist and Senior Advisor, CARE International

Learn more about Pankhursts’s great-grandmother Emmeline Pankhurst and grandmother Sylvia Pankhurst, both leaders in the suffragette movement.

Bill McKibben, Co-Founder, 350.org and founder of Third Act

Instagram | Facebook | Twitter

Twitter | Facebook | LinkedIn | Facebook

Gail Bradbrook, Co-Founder, Extinction Rebellion

Twitter | Facebook | LinkedIn |

Jerome Foster II, Co-founder of Waic Up and youngest Member of the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council (WEJAC)

LinkedIn | Instagram | Twitter

Adam Kahane, Director

Twitter | Facebook | Instagram | LinkedIn

LinkedIn |

Charles Ogilvie, previous Director of Strategy for the Cabinet Office for COP26

LinkedIn | Twitter | Instagram

It’s official, we’re a TED Audio Collective Podcast - Proof!

Check out more podcasts from The TED Audio Collective

Please follow us on social media!

Full Transcript

Transcript generated by AI. While we aim for accuracy, errors may still occur. Please refer to the episode’s audio for the definitive version

Tom: [00:00:12] Hello and welcome to Outrage and Optimism. I'm Tom Rivett-Carnac. Today we bring you a special episode looking at the challenges and opportunities of different philosophies of change inside the climate movement. Thanks for being here. So this week we bring you the first in a special two part series exploring some of the tensions we've recently observed within the climate movement. We're now a quarter of the way through this decisive decade, and with progress still woefully lacking, it's no surprise we're seeing a greater degree of anxiety and call for more urgent, immediate action. However, some argue that using disruptive tactics used by protest groups risks alienating many from the movement at a time when we need everyone and that a more pragmatic approach is now what's necessary. In this first episode, we'll be looking at the divisions and also asking if both approaches are ultimately needed and if so, how they can collaborate. We'll be speaking to a number of guests with deep, personal and professional experience of this issue. First of all, from an activist and direct descendant of the founder of the Suffragettes.

Helen: [00:01:30] The Constitution lot felt that it would delay that the antics of the suffragettes, the militancy, would put people off and was dangerous and detrimental to the cause. And the suffragettes thought that this slowly, slowly, quietly, whatever was just kowtowing. And and part of the problem very much that women themselves following those views were part of the problem.

Tom: [00:01:52] To a co-founder of Extinction Rebellion.

Gail: [00:01:55] Tactics and strategy are different. You can have a strategy for an overall ecology of movements and I think that's where we are now, that we need to think globally and strategically for an ecology of movements and tactics can be different therein.

Tom: [00:02:11] And the Chief Political Strategist for the UK Government and COP26.

Charles: [00:02:15] We need to believe that some of this corporate momentum is real and we need to know how as a climate movement we can support that rather than just attack it. And that is a very difficult set of distinctions to make.

Tom: [00:02:37] So, listeners, you might remember we interviewed former Conservative Minister Rory Stewart back in November 2022, and he now hosts, of course, the successful podcast, The rest is Politics, alongside former Labour communications director Alastair Campbell. And they decided to join forces across the political divide to bring back the art of disagreeing agreeably. And this really resonated with me as I thought about the struggles we currently have within the climate movement. So I asked Rory whether he recognized the dichotomy between those trying to drive momentum and those who insist on perfection and the resulting battle that inevitably occurs.

Rory: [00:03:15] Yeah, absolutely. I think that's entirely true. And I think there is a level of I mean, it goes to the heart of different types of philosophy. I mean, I obviously come from a centre right tradition. I come from a conservative tradition that tends to emphasize pragmatism and evolution rather than radical idealism. And I often feel, obviously in my whole life that sometimes very radical, aggressive ideas are, get in the way of progress. They create a sort of vision of perfection and optimism, which is pretty close to despair because it returns to where we began, which is the question of engagement with reality. It's as though, people don't want to talk about trade offs, don't want to talk about power, don't want to talk about sacrifices, Don't want to talk about difficult yeah, difficult choices between lesser evils. And if you are not prepared to get into that conversation, you can feel good about yourself and feel very pious and feel that the whole world is refusing to listen to your great prophetic vision. But you're unlikely to change anyone's life. You have this sort of delight of purity without impact.

Tom: [00:04:42] Yeah. Fascinating. Okay. Thank you. So Rory's description on the need for pragmatism and evolution resonated with me, and it really made me remember these challenges that we've been facing in the climate world. We've got some amazing interviews for you. We're going to dig into this and explore the history and what's really happening here. And do people agree with this and what else can we do differently? But I wanted to share this journey with someone else who inhabited a similar philosophy to me, but maybe with a bit of a distinction. So we could talk around the middle of where we are, but with a bit of change. And also somebody who brings a different perspective from a different generation. So I'm delighted to introduce Fiona McRaith. Fiona is a colleague and a friend. She works at the Bezos Earth Fund and she'll introduce herself in a minute. But she is of a different generation to me, I'm guessing there's probably two decades that separate us in age. Fiona, we'll find out in a minute. But I've been so impressed at Fiona's pragmatism to get stuff done, but also her willingness to appreciate people from different points of view and to incorporate those different points of view in how we move forward. So Fiona, welcome to Outrage and Optimism. We're delighted to have you here.

Fiona: [00:05:54] Thank you. It's really a pleasure to be here.

Tom: [00:05:57] So we're going to go on this little journey together and explore this philosophy. But first, the listeners are going to want to know who you are. So give us a couple of minutes on who is Fiona?

Fiona: [00:06:06] Yes, I will do my best. So as Tom mentioned, my name is Fiona McRaith. I work at the Bezos Earth Fund. Previously I was at the World Resources Institute, a data into action non-profit. And at both those places I've supported the President and CEO, Dr. Andrew Steer, and that's been a very interesting perch. I joined WRI right out of college. Tom's right, there's probably about two decades in between us. I'm now five years out of college and, in my mid 20's and.

Tom: [00:06:37] I'm in my mid 40's so I was right. Yeah.

Fiona: [00:06:39] There we go. And I've seen, of course, from an NGO and now a climate philanthropy, a lot of different perspectives. But interestingly, when I was in high school, so now about 12 years ago when I was 14, I became, I wouldn't have even called it a climate activist until recently, but I became someone who was a peer educator on global warming to folks my own age. I would go from high school to high school in the city of Chicago, where I grew up talking about global warming. We had this great video of cows releasing methane through their farts and burps, and it was this really kind of wonderful thing. And from there, I became more connected to the climate movement. And I, in 2013, I was a junior in high school, and I marched on Washington with a guest that we will hear from later in this episode and against the Keystone XL pipeline for oil and gas. And from there, you know, university more activism with the divestment movement. And then I had the privilege of working in the final summer in Obama's White House. And this was an era of great optimism. We thought we were paving the road for the first female president who would be a leader in climate and nature. And of course, we all know that didn't happen. So I've always kind of, from a personal perspective, wanted to do the most I could in the way that felt the most authentic. And that's how I've that's a long story short, but how I've landed here and doing what I do now.

Tom: [00:08:11] Okay, so, so that's fantastic and amazing history in your life. So I want to ask you a thought experiment question, and I would encourage listeners to engage in this as well. You have been given a great task to change the future of humanity, and you've got to work out how you're going to approach that task, what you're going to do. And there's two philosophies of change that you could take. One is you could say, all right, I now know what my task is. I have moral clarity in the tradition of the great moral leaders of the past. I'm now going to say I'm going to hold firm to this outcome. I will not be moved. This is the hill I die on and I am going to refuse to be shifted from this perspective. Now, that will be complicated in the way it lands in the world, right? Some people will be inspired by your moral clarity. Others will be put off. They'll say, you're young, you're naïve. You're not realistic. You're not focusing on the way the world works. So that's one approach. The other approach is you could say, okay, now I know where I'm going to go. I'm going to take the first step to try to get there. And that first step will create another first step and a second step. And the second step will create the third step. And I will iterate my way step by step towards where I need to go. Now, that enables you to get started, but how do you know you're not going to get lost along the way? How are you going to hold your clarity of purpose across that journey? How are you going to be sure that you're going to end up where you know you need to end up and not get confused by the world? That's a theoretical, philosophical question. But as you know, because we've been preparing these podcasts, that's also a practical consideration. The climate movement has different people choosing different philosophies. The first question is where do you fall?

Fiona: [00:09:54] Yeah, I mean, I will answer my initial response and then I will share a little bit about, whenever Tom decides to ask you a philosophical question, you just realize you'll never have a good enough answer is what, what part of my answer is. But, you know, I fundamentally believe that the transformation of systems is required when you face any big problem, because fundamentally the problem exists because those systems have failed. I think ten years ago, eight years ago, five years ago, I would have believed that it wasn't just transformation of those systems. It was a complete dismemberment and rebuilding of those systems. I think calibration and transformation are very possible. And to answer your question, I think that you can't actually do that unless you fundamentally rethink the way that you're building them. So not about speed, but about integrity. So I think in the, if I were to fall ideologically, I would err more on the side of integrity or the perfection theory of change, because I do not believe that's how it's been done in the past. And I think part of the biggest problem that we're that we see is that there's such a lack of trust. And I think only when you approach things with with integrity can you find that trust. How about you, Tom?

Tom: [00:11:19] That's a good answer. So so when I was younger than you more than two decades ago, I was a sort of idealistic activist and the concept of carbon neutrality and this was in 2004/2005, emerged in the UK and as somebody in my early to mid 20's, I was completely morally outraged by the idea that these companies would potentially continue to pollute and and purchase offsets. And so I got fully engaged in the campaigns to stop this. And a friend came up with this brilliant idea called Cheat Neutral that I got involved in. This is the idea that you can pay someone else to be faithful to their partner in order to make up for your own infidelity. Completely different and so.

Fiona: [00:12:01] Completely bonkers.

Tom: [00:12:02] So evidently different that it poked fun at this concept of offsetting. But the key point is we tried to make it shameful to engage in offsetting. We tried to tear it down, with many people, I don't claim it for myself, many people did this together and in the end we were successful in 2006, 2007. But then something changed in me because what happened next was, not very much. Rather than people going and doing it perfectly, they stopped and everyone disappeared again and stopped taking action. So years later, I began to wonder, was that really a great thing I did there, to focus on that perfection? And then with Christiana, I was engaged in the Paris Agreement and that was very much about momentum and joy and building opportunity and this big wave of momentum towards an outcome. And we delivered the Paris Agreement and it was great. And now some years later, we've got this challenge that not all commitments are being met. Um, you know, are they all really made with the best of intentions? So I'm dancing around these two things and I think the reason why I've been so keen to do these episodes is because I genuinely don't know the answer. I think there are risks in both, and I hope that this week and next week we will go some way towards trying to unpick for ourselves and for the climate community really what's needed here. So unless you've got anything else to add, I'm going to kick us off.

Fiona: [00:13:26] Tom, you honestly laid it out so well. And I feel just, you know, these next two episodes will be really fun because the entire time we've been exploring this, I've felt myself, you know, like a pendulum between the two and I, and it will be fun to to talk this through and listeners to hear from you what you think as well.

Tom: [00:13:45] All right.

Fiona: [00:13:45] I am ready to go.

Tom: [00:13:47] So first thing to say is that obviously it would be hubris, and I'm guilty of that, to believe that we are the first people to face this issue in history. So one of the first things that we wanted to do was to go back and talk to somebody who had the institutional, or maybe family memory of how we have collectively as the human family dealt with this before, and who better to kick us off than a descendant of the leaders and originators of the suffragette movement who in the UK created the movement that actually led to the right to vote for women, which, let's remember, is barely a hundred years ago. A committed activist, Helen Pankhurst, she's also the great granddaughter of Emmeline Pankhurst and the granddaughter of Sylvia Pankhurst. Helen Pankhurst, it is such a privilege to have you on Outrage and Optimism. We're really excited to talk to you, and I'm just going to give a word of background as to why we're so excited about this conversation. One of the things that occurred to me was the arrogance that I was exhibiting by assuming that we were facing this problem for the first time. And of course, this issue is as old as the hills as people have been trying to solve this issue. And no one is probably better placed than you, with your family history, with the history of the suffragettes that you've witnessed and studied. So I would love to just start off by inviting you to reflect on what I just said and also any lessons that you would have taken from your family and from your your learning that relate to that.

Helen: [00:15:17] Yes, thank you. And really glad to be with you and to be reflecting together on these issues. As you said, people caring passionately about something that needs to change, starting off together and then splintering and having different views and infighting is very much part of, I think, caring deeply about anything. And I think also having the more radical and the less radical group is probably part of the pattern. I think having the more democratic and the more authoritarian likewise. And I think reflecting across those differences and the strengths and weaknesses of the different approaches is interesting, as is the, well, what could we do better so that this pattern doesn't actually result in the loss of the whole campaign. Um, if I think about the suffragette movement, I mean, first there was the schism between the suffragists and the suffragette. Suffragists, constitutional suffragettes formed in 1903 with the view that the constitutional road was too long. It just wasn't getting us anywhere. The wrong people were engaging, meaning too few people were engaging with too restricted a background, the social economic background, and that it was time to demand not nicely request change. So a lot of parallels already in what I'm saying. So the split between the suffragettes as the more demanding voice. But then wait a little bit and then you have the splits within the suffragette movement with the Women's Freedom League in 1907 going off and doing their own thing because they get frustrated with the non-democratic way of doing things and to some extent with the level of militancy.

Helen: [00:17:08] But then interestingly, they themselves get quite militant and you could argue that they themselves don't really hold on to the issue of Democratic decision making question mark. And then you also have in 1914 the formation of the East London Federation of the Suffragettes with Sylvia, my grandmother splitting, being forced out in her case, being forced out because of Emmeline, her mother, and Christabel, her sister believing that they should lead with their ideas not questioned, and Sylvia challenging that and having more democratic instincts. Also uncomfortable with the level of militancy and particular the destruction of art, Sylvia as an artist. And also feeling that who is being represented is problematic, feeling that the voice of the working class isn't as visible as it needs to be, because fundamentally it's their interests which is most marginalized in the cause. So I think already many parallels, not just between the constitutional and the militant, so not just between the long standing green movement and the climate activists, but then within the climate activists, the different flanks and views about how you proceed and then the bitterness that happens in our case, in my family's case, Sylvia and her mother and sister end up not speaking to each other. There's a massive rift. The media get involved. It's it's as emotive as it possibly can be, even within a family.

Tom: [00:18:42] And what's fascinating about that is, you know, that's people who want the same thing, right? I mean, they're working for the same thing as is also the case now with this terrible issue of climate change. But but yet we think back on the suffragettes inexpertly as one movement. So can you talk any more about the ultimate success of the ideal and the relationship between those two flanks? Because it strikes me that both are needed, but somehow we don't accept that.

Helen: [00:19:10] Yes, I think that's right. I think both are needed. And my first plea, if you will, to anybody listening to this is, however much you differ in tactics and even to some extent in the prioritization of goals, finding moments of collective action and moments where you put aside those differences to represent that wonderful width of perspectives and approaches is absolutely critical. So go off and do your own things and argue and all the rest of it, but find moments of collective voice. To some extent, there's examples of that within the suffrage movement. I would say that the 1908 Women's Sunday March event in Hyde Park, where they managed to get something like 500,000 people attending, massive numbers 1908, it had never been those numbers had never been seen before, and it was done partly because the government challenged, I think it was Asquith, challenged the suffragette movement, saying not many people care about your cause. It's not a big thing. And so they said, we'll just show you how many people care about this. And then sadly, the other moments where there was probably a collective coming together are the points of hurt and death. So Emily Wilding Davison's death in 1913 and Black Friday 1910 brings together not just the suffragettes, but also the suffrage campaigners to say these are awful events. And again, I suppose looking at the environmental movement, one would hope that these moments of coming together are collectively organised and are not the consequence of some really horrid event.

Tom: [00:21:07] Just one more question or observation on the parallels is, one of the things we see in the climate movement is that both of those camps and we're, you know, exaggerating this for the purpose of having this discussion, almost see the other as being detrimental to their goals, not just ineffective but detrimental. So those who are working on, you know, pragmatic solutions will say, well, activists are turning off the majority of the population and so therefore they should stop. It's detrimental. And activists will say, you know, those who are engaging and looking for step by step solutions are apologists for the capitalist system and will never actually make progress. So they actually do see each other, to some degree, as a principal enemy because they're actually stopping progress. Is that similar, I mean, your your distinction there between constitutionalist and democratic approaches to universal suffrage? Anything in there that rings any bells?

Helen: [00:22:00] Yes, a lot. I mean, the Constitution lot felt that it would delay that the antics of the suffragettes, the militancy, would put people off and was dangerous and detrimental to the cause. And the suffragettes thought that this slowly, slowly, quietly, whatever was just kowtowing. And and part of the problem very much that women themselves following those views were part of the problem. And so my call to any people listening involved in the environmental movement is, you know, believe passionately in your bit of the story. But unless you support the wider puzzle, you know, if you think about a jigsaw puzzle, you've got the different bits. You have to believe that you're part of humanity and those on the side of wanting to make a difference.

Tom: [00:22:48] I'd love to just ask about the sort of, the role of extremism in movement changing sort of more specifically. So we're now seeing obviously, you know, a greater degree of anxiety around the, around society and a sense that it's kind of too late. You know, we're a quarter of the way through this decisive decade. And as a result, more and more people are turning to that type of action that is entirely understandable and is risky from a movement building perspective. Um, how can we have that approach and have it deliver what it wants to deliver based on historical examples rather than take us back the wrong direction?

Helen: [00:23:31] Yeah, that's a really interesting question because I think what you have with the suffragette movement is a ratcheting up. So the suffragettes say, this is ridiculous, nothing's happening. Let's do deeds, not words. And the deeds, not words, it's not just for their activists. It's also saying to government, come on, you've promised, you've promised, and nothing happens. You've got to deliver with a deed. So deeds, not words, is both for the opposition, if you will, the government and also for the activists. Let's do more. Let's let's go out there. Let's make the change. So you have that. Then you have the government bringing in increasingly restrictive, using using the police, sometimes formally just using the police, sometimes actually instructing the police to be even more aggressive. Black Friday, they were told to abuse the women in essence. You have the women then getting really angry with the approach and saying, okay, well then we will step things up. We will, we'll throw stones. You have the government imprisoning. You have the women saying, okay, we will go on hunger strike, you have the force feeding, you have deaths. So in any movement like this, there is a ratcheting up as the sense of dismay with the reality, as the sense of urgency builds up, as the government tries to control and brings in more restrictive legislation and more attempts to control and silence. Again, the parallels with what we're seeing in the environmental movement. How do you stop that? I don't know.

Tom: [00:25:08] Or should you? Maybe you shouldn't. Yeah.

Helen: [00:25:10] Yeah, yeah. I mean, I think the most radical people would say that you need that in order to change because otherwise it's acquiescence and delayed action. I think other people would say, yes, but are you losing support by doing that? And isn't the building of more support, more engagement by more people the ultimate way to get the change? And I don't know that that's the live debate.

Tom: [00:25:50] So, so interesting to hear this historical perspective from Helen. She's clearly been steeped in this history of ways in which these movements have and haven't been successful in the past. And one of the things I take from that is that it seems important to celebrate this diversity of approaches, but actually it can be toxic and difficult to live with. Where were you at the end of this conversation? What are we learning so far?

Fiona: [00:26:16] Yeah, as as an American, Helen, I hadn't heard very much about the suffragettes. So it was it was really cool to even learn about the fractures through the process of that movement as well and kind of actually feel soothed by by it. I do think that as we've listened, I think that the role that different people play is so valuable. And the mistake might be thinking that everyone has to agree that that that person's role is is valued. Really, there's just a she talked about it as well. There's a humility of trust that everything is actually needed. The the more radical or extreme or kind of activist to to one spectrum. But you also need real pragmatic folks who just want to make progress. And I think what we're missing in trying to parse out is that can all of those exist and drive forward the same objective. And and Tom, I wonder maybe you, I think those shared moments of celebration are powerful. If everyone can celebrate one thing I mean, around Paris, I wonder if you felt that so many different types of folks were able to celebrate this success that was needed.

Tom: [00:27:31] Hmm. Well, it's interesting. I mean, you know, the suffragettes analogy with Paris, there was a binary moment that they were working towards. Right? You know, you got the law passed, we got the global deal. And there's even though that's difficult, it has an emotional simplicity and a sense of jeopardy to run towards this moment. But actually now it feels a little more complicated, right? We're just trying to do a million things and do them well.

Fiona: [00:27:55] Yeah.

Tom: [00:28:42] We've got a great next conversation which will take us deeper. And someone who brings an unbelievable legacy of campaigning is Bill McKibben. He, of course, co-founded the first global grassroots climate campaign 350.org, who, speaking of Paris, were incredibly important behind the scenes in Paris and more recently set up Third Act. Now, I think you know Bill from years ago. Is that right, Fiona?

Fiona: [00:29:04] I do, yeah. I was a youth activist and marched with him in 2013, ten years ago this month.

Tom: [00:29:11] Nice. Which, Bill's been doing this many more decades than that, I know that's a large percentage of your life, it's not a big percentage of Bill's life. Okay, so.

Fiona: [00:29:18] Indeed.

Tom: [00:29:19] He knows what it takes to sustain momentum over the long term and bring it to a successful close. Fiona began by asking him if he thought remaining hopeful played a key part in this.

Bill: [00:29:31] Let me begin by saying I do not think that either writers or activists really owe anybody hope. Our job is not to make people feel better about things. That said, I mean, what we owe is honesty. And honesty always has room for what can happen next, what can still be done. There's lots of things that have been foreclosed at this point. And we're past the point, obviously, where stopping global warming is an option on the menu. We're at the point now where we're trying desperately to limit damage. That's not as you know, that's a that's in and of itself a there's a there's a sort of despairing note to that. It's not like I have a dream. It's like maybe we can avoid some of these nightmares if we get to work. And and but but that's where we are. And, and you do have to be able to, I think, in order to motivate people to do the work that needs doing, you do have to be able to give people a plausible picture of how their actions might add up to something real, tangible, useful. Part of the fight is always just figuring out, you know, how you can have a fight. So, you know, for a long time it was very difficult to figure out how to even take on the fossil fuel movement, the fossil fuel industry, because it's so big. That's the reason we did these divestment campaigns, was because it allowed it to happen in 10,000 different places. Most people weren't near a coal mine or an oil well, but everybody was near a pot of money, a university endowment, a pension fund, something that you could then have the fight there. So it's it's there's never any master stroke that gets it all done. You know.

Fiona: [00:31:31] I wonder if you can share your your perspective on how Third Act and folks from a different generation older folks can lend insight to these challenges to help help young folks in this movement kind of transcend them, knowing that all of it is young, as you said.

Bill: [00:31:48] Sure. I mean, young people have really done most of the work. I mean, I started 350.org with seven college students. That was the first global grassroots climate campaign. The divestment campaign that we helped launch was mostly college students. When they got out of college, they formed the Sunrise Movement that brought us the Green New Deal and passed the Climate Bill. And, you know, across the pond, it's been junior high and high school students, the sort of Greta Thunberg. And there's Greta, who's one of my favourite people to work with, would immediately say there are 10,000 Greta Thunberg's around the planet and they have 10 million followers. That's how many kids were out on school strike. So the kids are doing what they should be doing and and for understandable reasons. I mean, I'm going to be dead before the worst of this kicks in. But if you're 20 right now, you're going to be in the prime of your life when we're at the absolute nadir. The thing that worried me, though, was that I heard too many people saying, well, it's up to the next generation to solve these problems, which seems a, ignoble and b, seems impractical. Young people lack some of the structural power that we need to make change. Older people are a great constituency to work with because there's a lot of us in this country, 70 million people over the age of 60. Multiply that by some factor because we all vote. There's no known way to prevent old people from voting.

Bill: [00:33:14] And we ended up with most of the money. Fair or not, boomers and the silent generation above them have about 70% of the country's financial assets. So if you want to take on Washington or Wall Street, good to have some people with hairlines like mine. We're very conscious about the fact that we're not trying to lead. We're trying to help and support and push. So we're ready to to play our part. And play it well. And, you know, frankly, we have some experience in this if you're in your 60s or 70s or 80s now, your first act was when we were actually making extraordinary social, cultural, political transformations in this country back in the 1960s and 1970s. We have muscle memory of that. And, you know, those are the things that the right is targeting at the moment. I mean, look what the Supreme Court went after the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the Gun Control Act of 1968, the Clean Air Act of 1970, the Roe v Wade 1973. These are things that people my age fought for and won. And and so, I mean, it's a good partnership and it's a lot of fun. And that's really, I think, an underrated and overlooked part of successful movement building. It's got to be fun, energetic, enthusiastic, filled with art and music, filled with promise. You know, that's that's how we keep going over a long, discouraging stretches of time.

Tom: [00:35:12] So, I mean, who can't love Bill McKibben? He's just such an incredible force of nature for the future and what a privilege to talk to him and mean so much in what he said. But one thing is, there's such an underrated element of fun and energy and working together. And of course, if you approach anything your life, your activism, your work with those qualities, it becomes easier to collaborate and work collectively on big goals. What did you take from that, Fiona?

Fiona: [00:35:42] Um, exactly that. I mean, Bill has always been fun. Even when we were marching in 2013, we were talking, we spent at least a block and a half talking about pizza and different types of pizza. So it really is it's finding little moments and wonderful people. And I think that also feels very far off. I think there's such fear against the urgency and such a fear on both camps kind of of this puzzle that we're trying to to mould together is, you know, there's the perfection or the integrity. There's a fear that if you don't get it right now in this huge opportunity to remake the world, then it will never have a chance of being right, that we will embed inequity further. And there's this fear on the other side that if we don't get on with it, then we won't even have a chance. And I think in the face of fear, fun is often one of the first things that slips away. Um, and I, I mean, I was listening to him and just in awe and I do think youth bring a huge part of the fun and the levity and maybe older folks with more time and space, they also recognize that there's always time for fun. Um, so I was kind of thinking about that quite a bit. Bill is someone who, it seemed to me, and it's always seemed to me in my ten years of of getting to know him and observe him, he's someone who knows and trusts what his role is. And if we all could just know our role with that clarity, I do wonder what it could mean for the movement.

Tom: [00:37:17] People can relax, I think, more when they know their role and then they fit together in their niche and they can collaborate better. It's really hard to be open and collaborative and energetic and enthusiastic when you're working on an issue where you feel like you're running out of time because that in itself creates a sense of scarcity and breathlessness. It's something I've observed in the climate movement over the last few years. There's this sort of sense of breathless anxiety has emerged, which is making people feel understandably, and they should be right, there's nothing about us we're saying isn't right. This is right. They should be worried about the future. But it's really hard when you feel breathless and anxious to also feel like you want to have fun and energetic, which is partly what's exhausting us. Now, someone else who understands this tension very well is Gail Bradbrook. Gail is a former guest on this podcast. She has played a pivotal role in the climate movement in the U.K. as one of the founders of Extinction Rebellion. Of course, now known around the world. But she joins us now in a personal capacity. And I began by asking if she agreed with our reading of the current status of the climate movement as one split between moderates and radicals to the detriment of progress.

Gail: [00:38:47] I think it's not particularly useful personally because in actual fact they're both doing the same thing, which is asking the current system to make changes. And I don't think the current system, the current economic and political system, which is deeply captured and corrupted, is capable of making the kinds of decisions that need to be made. And so they're actually relatively moderate approaches. And then also, I would say that the word radical one might want to associate with moves to commit acts of sabotage. And I think in these times when the system won't change, that sabotage actions are quite appropriate, which is a controversial thing to say. Uh, it's not for Extinction Rebellion, by the way, to do sabotage actions because we're what you call an above the ground movement. We do acts of civil disobedience and we take accountability for our actions.

Tom: [00:39:54] But is there a risk that acts of civil disobedience can discourage some who would otherwise join the climate movement?

Gail: [00:40:01] It's often said that people are alienated by tactics, and that's not the point of civil disobedience. The point of civil disobedience is to get a subject talked about whether people like the tactics or not that get it talked about. So it's not like I particularly like the idea that anybody's feeling alienated, but that's slightly missing the point of the purpose of of civil disobedience. I think what we need in terms of sustainability moves environmental, social governance and so on is radical honesty.

Tom: [00:40:34] There are a lot of people working in corporate sustainability who are trying to change their companies. That can often be quite a lonely job. What they are potentially, at their best going to do, is try to make them more carbon efficient, focus on the circular economy, drive down their emissions. Would you see those people inside those corporations as allies of your movement. Or would you say that actually they're sort of stopping you from being as successful as you could do by providing providing an impression that that's all that's needed?

Gail: [00:41:09] You know, I really think it's up to those folks to be clear with themselves about the value of what they're doing. And when I've had ESG people saying to me, I've done this job for this many years, my friend has worked in Shell for 15 years trying to get sustainability projects through, and unless they're profit making, they all get scrapped. You know, when people say things like that, I think each person needs to look at the reality of their own jobs. And we've also had people behind the scenes saying to us that we are making their jobs easier. People in the banking sector of whom we've broken their windows. Right. So we know that they're trying to do good things. So I don't think you can make a blanket statement to say it's all good or it's all bad. I think people have to take an honest view of what they're doing.

Tom: [00:42:02] So, um, so interestingly Gail, XR recently promised a temporary, this is a quote, a temporary shift away from public disruption as a primary tactic to prioritize attendance over arrest and relationships over roadblocks. Um, and so I'm just curious to know why that changed. Does that flow from a belief that the public are being alienated and we need to have a more inclusive approach? Does it flow from an evolution of your strategy? Because it's quite a departure that, it's quite an interesting thing for an organization like XR to do. It must have been an interesting process of dialogue internally.

Gail: [00:42:43] Extinction Rebellion has ten different principles and values, and one of the most foundational ones is the idea of regenerative cultures, you know, and that is partly focused on building community and connections. And it's been very under focused upon. And our principle number two, that's about civil disobedience gets over focused on. So I think it's just a re-emphasis. I think it would be even more effective to talk about relationships and dialogue and so on through coalition building rather than making announcements that catch people on the on the hoof. So, um, yeah. And I think with like with many things that Extinction Rebellion does, it's quite experimental and many of us are watching to see how, um, impactful it is. But I really don't think it came from the idea that public disruption is ineffective. I think we've seen time and time again that it is effective, but depending on what it is you're trying to achieve. So I think what, another thing that the movements are at risk of is getting stuck in a sort of repetitive mode of of something that works one time doing it again because it worked that time or it appeared to have an impact. And I guess I get in some frustration, as I've said, about the depth of the analysis that that kind of thinking is based upon.

Tom: [00:44:29] So, I mean, Gail is clearly such a leader in this space. What a privilege to have her back on the podcast. And what's interesting about that is that even amongst those who are collectively very clear that they want to participate in direct action and activism, it's still hard to keep movements together. There's still a multiplicity of perspectives and you still need to focus on connection and community. Where did you end up after that?

Fiona: [00:44:52] Yeah, it's been interesting. We've heard the value of fun, of community, of collective action over and over. And I think Gail, really by just looking at one community, what I think of as a cohesive community, the the different fragments, Helen was saying the same thing. Trying to zoom out is such a powerful tool and often one that's so hard in the face of urgency or integrity. But when you zoom out, you can often hopefully find that the end goal is very similar, if not the same, and if you might have different ways of describing it or different things that you emphasize. But you know what I want is, is the same as what you want and let's trust that and we'll have a party when we get there type of thing. But I think that's what's missing so much is is the trust.

Tom: [00:45:44] Yeah. And zooming out to see how change happens in unexpected ways I think also gives you space to realize that that that radical transformation does occur. And we don't always know the impact of our actions. And I think XR has actually been a great example of that in the UK. And when you can zoom out far enough to see how change happens in unexpected ways, it can be really inspiring and it can give you the space to take a more generous approach. Now, Fiona, we're going to go now to an interview that you conducted by yourself. And this is actually great because we've now heard from campaigners like Gail and Bill. But actually, it's young people who've been the real driving force behind the climate movement. And you recently caught up with one of the brightest stars. Jerome Foster II. What do you want to say about Jerome before we hear from him?

Fiona: [00:46:35] I mean, he's just a rock star. It's a, it's a fun interview. It was, we went down paths that I didn't think would be relevant, that were and I think that's part of the beauty of what we're learning, that in a fight like this against climate change, it's so encompassing that your greatest friends are folks that you've bumped into at conferences or in the streets. I have such admiration, respect, and I have a lot of fun when I'm with Jerome, which I think is kind of the special sauce.

Tom: [00:47:06] Nice. Yeah, Yeah, I agree. And we should just point out that. So Jerome is the youngest member of the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council. You'll hear that referred to as WHEJAC in this interview. And together with his partner, Elijah McKenzie Jackson, he recently co-founded Wake Up, which is a communication to action organization designed to inspire and inform those wishing to sign up for meaningful climate action.

Jerome: [00:47:34] The biggest thing that we wanted to do is make sure that people don't just see that that instance of taking action is the only thing they can do and kind of build beyond that. To have a journalism piece where people are able able to understand what's happening within these movements and figure out how they can contribute, especially when we talk about the link between perfectionism and mobilization. Oftentimes it's about making sure that we have progress every time we go into these these these meeting rooms. And I think that when we meet with elected officials, they always talk about the perfection of a bill like the Climate Climate Change Education Act wasn't ready because, oh, we need such here, we need in this paragraph we need more and more investments and such and such to get the senator on. But really, it's all about how do we make sure we're accountable to our constituents and that constituents have the power to say yes or no about these bills, because at the end of the day, they're working for the people and not for the corporations that are buying them out, really. And I think that is the biggest change that we've seen so far within Wake Up is making sure that we're not just pushing for the next event, but making sure that we have momentum within communities at the local level so that we're going out and meeting them where they are and not just trying to get them to go to an event, but meeting them in their homes really.

Jerome: [00:48:43] The most important thing I've done so far I've seen is a part of the WHEJAC is we launched the climate and economic justice screening tool. We're able to map disadvantaged communities across America. And that's an exact example of what happens when you have youth power and young and young people in marginalized community at the table. Because what we do with that power is bring accountability and bring transparency to these systems of of governance. For example, this tool now will allow people to see what how they're impacted by the climate crisis and what actual metrics you can see from air quality to exposure to toxic toxic air pollution to PM2.5. And one thing that we're now pushing for is for it to actually include community power to say, hey, I see I have increased exposure to air to toxic air pollution. What measures are you taking in place? So we have a measure, a button where you can actually send response back to the EPA and say, what are you doing? And have live tracking where they're able to see the updates and those investments. And I think that's really what's key is keeping momentum and keeping them accountable, because that momentum only comes from having that push and pull and the power being in the hands of communities.

Fiona: [00:49:47] So in many ways, it sounds like one of the things that could actually bridge this divide is the role of accountability and the role of data and measurement to provide that accountability. So even if you have momentum, you actually have some tools at hand, which is of course, media voices, but also the measurement. I'd love to talk a little bit more about the screening tool because this also was, even just launching this was perhaps a perfect case study to needing a tool and really wanting one out there, but also knowing that it would not be perfect and a lot of people, there were a lot of voices that said this is deeply imperfect and shouldn't be launched. Could you share a little bit about your perspective being on the WHEJAC in the launching of that and and how you think, it sounds like it's evolving to address that, but just maybe a little bit to dive into that case study?

Jerome: [00:50:39] Absolutely. When I first joined the WHEJAC, the first council that I was on was the Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool. And the biggest thing that we wanted was to include race in that screening tool. And because of the fact that there were certain laws and, laws and regulations around, including race, we weren't able to do that even though we pushed multiple recommendations looking for it. Because when it comes to environmental injustice, race, race is the most primary indicator. If it wasn't for race and racism, there wouldn't be climate injustice at the disparities that we see today. And one of the things that we're pushing for in the 2.1 version of the tool is to include race indicator, is to include, make sure that marginalized communities are seen in the forefront so that when we look at our communities, they reflect the actual problem and getting at the roots of it. But one way in which we've gone around that is by including redlining data and also including unexpectedly tree cover data, because as a result of redlining there has been a lack of green spaces in communities. And when we mapped access and and green spaces, it matched 95% of the time to a black versus a white community. And that was another indicator of how do we reach perfection, even though there might be hurdles along the way, let's look for other data sources that are tangential to the problem, but indicate that route in another way. And I think that's another thing that Wake Up is doing too, is by partnering with data sources and data communities to make sure that communities that are oftentimes underrepresented, like Alaska native communities and indigenous communities that often aren't don't have data covering these issues are represented in the Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool.

Fiona: [00:52:15] I'd love to hear a little bit about the way in which, like the personal element of this story, like how have you personally navigated, as someone who's been you know, doing podcast interviews for years as a, as the youngest member of the WHEJAC is now launching a new organization on the back of one that you championed so beautifully. How has that been and how have you maybe on a personal level, also felt the tension between the momentum and perfection and kind of identity?

Jerome: [00:52:46] Yeah, I think growing up and being around 13 and 14, I transitioned from just like talking about climate change to my classmates and like my parents to actually talking about it with my community. And the biggest momentum and push was to advocate for climate policy and to have like the Clean Energy DC Act to be passed, or for the National Climate Bank Act to be passed in Congress at the time. And all those big things were like, oh, we got momentum. We have new legislation being introduced like the Green New Deal that would actually champion a ten year mobilization period. But the biggest thing that I realized is that we have to get at the root of who is actually impacting our political decisions, and that's economics. So we have to get to the root of how are we making sure that we're putting safeguards between our economic and political system to make sure we have true representation. And I think that has evolved from a personal level to me of kind of protesting and going out and protesting every Friday and doing 80 weeks in front of the White House and then going to Harvard University. I saw a difference because I went out to Weidner library on like a Friday and just meeting with the different different directors that were at Harvard, I saw that actually we need to go to their offices and we need to get their investors to stop investing in them if they don't divest from fossil fuels. And I saw instantly that two months later, after those investors start pulling their money away, they started taking action.

Jerome: [00:54:11] And that's kind of the shift I've seen is the perfection is how do we make sure that we're really pushing as hard as we can by having all four pillars of change happening with the young people we have are we're enormous social and cultural force. We create cultural moments every time we go out in mass numbers and change the social landscape and tell them that enough is enough. And that impacts policy to an extent. But if we don't use our economic buying power as a generation, that only goes so far. And that is the next push that we really want to to mobilize. And personally, for me, it's been a thing because as an activist, it's like, how do I support myself and how do I get a job? How do I do these things? And it's like, well, the real issue is like all these activists, like we're young people are now having to go off to college and university and look for jobs. Now we have less time to go out and organize in a way, and we have to make sure that when we go into workplaces, we're advocating for unions and we're advocating for really rooted change that not only talks about, oh, the climate crisis is really impacting communities, but what are we talking about, like communities at the front lines of things like how are we talking about race, how are we talking about LGBTQ folk. Because if we don't intersect all those things, we don't understand the broader picture and the broader system of oppression that still exists.

Fiona: [00:55:23] We've heard a lot about the role of collective action in healing and the role of fun and beauty and joy. And I think you and Elijah, more than most people that I've had the privilege to meet in this in this role, embody that. And I would just love to hear you talk about the role that that plays in your life and with Elijah and with your community.

Jerome: [00:55:47] Yeah, I met Elijah in like a year ago at this point, and it has just brought a sense of just community around me for, whenever I'm feeling sad about like a big event that just happened or happy and feel like joyous to be a part of this movement. I kind of have just like someone by my side. And I think that just underscores is really amazing because Elijah comes from a more direct action from like XR and organizations like that. And I come from just like organizing in the political spaces and like going testimonies and like trying to, like, push from that angle. And I think coming together, we saw like the intersections between those two things and saw like organizing in XR in London, they kind of have neighbourhood communities where they meet up every week and they do gardening and they just meet. And it's not even talk about like climate change sometimes they just just talk about how they're feeling. And I think that is really amazing as well as is building an entire community, not just around action and mobilizing and fighting for change, but seeing community care, because that's really what our our world has to be built on. It's just that sense of joy and that sense of solidarity amongst your neighbours and your community, really.

Fiona: [00:57:22] So, Tom, something that was really interesting for me that Jerome was talking about. He's the youngest member of the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Committee, and he has community, obviously, then that are decades older than him. And they're articulating these really tough things within a government structure that might not have the fundamental understanding that we wish it did for what is needed for equity and justice across climate in the United States. And he also talked a lot about community and community with his partner, Elijah, who who they're both young and I, and I think that oftentimes folks like Jerome, who are who are youth activists in this space, that is really even though youth activists get a lot of the attention publicly or might have a great following, they they are the minority in a lot of cases. And they are the ones that we look to, we heard with Bill, to infuse fun and energy and often bring us this collective action moments, these marching on the streets. But yet they're also asked to do, to carry such burden and I just. What do you think, Tom?

Tom: [00:58:32] So I mean Jerome is clearly such an incredible leader and able to bring people together on these remarkable outcomes that he's driving towards and participate, I mean, with incredible maturity in these complex discussions. I think that we we lose focus on community and connection at our peril. I think that this is difficult work that is going to take these young people the rest of their lives and they know that. And that's overwhelming and is exhausting and it has potentially devastating consequences for their whole lives. And we see all around us the evidence of how detrimental that can be to mental health. More than 50% of young people feel that humanity is doomed in the short to medium term. More than 60% think about climate change for multiple hours on a daily basis. And how do you deal with that? Because you can't tell them that they're wrong, because they're right to be that worried. It has to be about the qualities of human engagement to try and manage that. And I think when you get the qualities right, it's to do with connections, to do with understanding, is to do with conversation, simple activities that people take place together. Then different theories of change can unify and we can be a community of transformation. So our world is so used to quantities, you know, if you can't measure it, then it doesn't exist. But actually what we're remembering here is it's qualities that bring us together. It's human qualities of connection that make us better at trying to change the world. And actually, that brings us to an interesting point. So the next person we're bringing on here is Adam Kahane. And Adam has had an outsized impact on my life. He wrote a book called Power and Love, which in many ways is sort of the precursor of this dichotomy that we're talking about. And I would really recommend it to people. He's now the Director of Reos Partners, and he helps people move forward together to deal with the most important and intractable issues of our time.

Adam: [01:00:27] The bulk of my work has been with people facing very difficult issues across very deep divides. As you know, I got started in South Africa amongst politicians and business people and activists trying to help make the transition from apartheid to South Africa. I've worked in civil war contexts on complex environmental issues, and and then my colleagues and I have worked a lot over the last few years on climate, which has certain particular characteristics, especially the the question of urgency. And in doing all of that, the question I've been trying to answer or have tried over and over to answer and I'm think I'm inching my way forward, is what works and what doesn't work in doing that or what's the orientation or the understanding or the approach that works or doesn't work. And, I think that there are some very common ways of understanding these situations that are unhelpful or wrong. The first is this idea that, uh, that there's such a thing as the whole. That we should focus on the whole. And I think it's an ordinary but very important misunderstanding. There's no such thing as the whole, except in some cosmic sense about all the matter in the universe or whatever. There's always multiple holes, and that's dreadfully important. I sometimes ask people, you know, there's a group of people from an, a movement or an alliance and a facilitator sitting in a room working together. There's only one or maybe two people for whom the success of the group as a whole is identical with their own self interest. And that's the facilitator and maybe the CEO. But for everybody else, you know, there's yes, that whole matters. But I've got my own organization and my department and my budget and my family and myself. And and so it's really important to recognize that. The, the second misunderstanding which arises directly from this is the idea that, um, that conflict is an exception which must be erased.

Adam: [01:03:07] And I don't think that's true at all. Once you understand there's multiple holes each doing their thing, what Bezos is trying to do, what Outrage and Optimism is trying to do, what the movement as a whole is trying to do, what I'm trying to do in participating here, then it's not surprising there's always going to be differences and conflict. It's not an exception. It's it's the rule. The third misunderstanding is that agreement is necessary to be able to advance and this is really not true. It's, I learned this from Juan Manuel Santos, the President of Colombia, through my work for many years, and who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2016. And I asked him once, why did he consider, why did he keep referring in his speeches to the work we had done 20 years earlier? And he said something remarkable that I never thought about. He said, the reason I constantly refer to this multi stakeholder dialogue called Destiny Colombia is because that's when I learned that contrary to all of my political and cultural upbringing, it is possible to work with people you do not agree with and will never agree with. And the example he gave was very telling. He said, when I was President of Colombia, Hugo Chávez was President of Venezuela. And when we met it was completely obvious we would never agree. I was a whatever, a liberal conservative or whatever he would describe himself. And and Chávez was a revolutionary socialist. But we were president of neighbouring countries. We had to figure out a way to move forward. Nonetheless.

Fiona: [01:05:05] Climate is a global issue, an intersectional issue that is being felt hardest by those with the least amount of power. And you, you've mentioned politicians a few times, and I think there seems to be, from my vantage point, just a huge absence of leadership. So how do you in a in a thing where everyone's lives will be touched in some way, how do you find the simplicity? How do you find the right messengers to convey that we don't have to have unity, but we need X, Y, Z? Like, how would you guide us on this path right now?

Adam: [01:05:43] This work of building alliances and not counting only and not expecting or counting on wise and powerful people from above to make the path for us is so important. The key, in my experience, is to be able to build relationships, human relationships. Because, as Carl Rogers said, what is most personal is most universal. And I come to the first point I made, I'm coming to think it's a misunderstanding that, the difficulty working together is mostly because of differences. I think that's a common misunderstanding. Equally often, maybe more often, it's because of similarities and competition for position, for who's going to be the thought leader for who's going to get the grant and that we're. So I think our our emphasis or could I say the emphasis in your question on differences may be may be exaggerated.

Fiona: [01:07:06] I thought this interview was so insightful and so different than some of the others of folks really embedded within a movement to hear from someone who studies them or supports people through them was, for me, almost a watershed moment in how I was starting to conceptualize what we're working at.

Tom: [01:07:28] Yeah, I agree. I completely agree. And I also liked, I think, that his analysis of how you don't need to agree with people to collectively move forward I thought was really good. It can be really tempting to think that agreement is a precursor to progress, but that's not the case.

Fiona: [01:07:44] Completely. That's one of the things I thought about as well. Just the process of progress can be messy.

Tom: [01:07:51] Yeah. And and and so human, right. How do you collaborate between different approaches trying to do big things? I think we can learn a lot from Adam. I liked I mean, you know, his point about exaggeration. I mean, I think the differences are real and they're serious and they're preventing us from moving forward in some ways or not, that's probably a wrong way to phrase it. They're not preventing us from moving forward, but we're not moving forward as effectively as we could in the face of an emergency if these things were structured differently. And I have to say, listening to him talk took me back to one of the conversations that actually first started the terrain of thinking in my mind, which was during COP26, when I sat down with the then High-Level Climate Action Champion Nigel Topping in the middle weekend. So can we just run that clip from Outrage and Optimism 18 months ago.

Nigel: [01:08:40] Well, first of all, I think recognizing that both of those realities are here, that on the one hand, there is a massive increase in ambition and commitment from governments, investors, businesses, cities, states and regions and and as real rage, frustration, scepticism. Justified because we're at COP26 and the emissions are still rising.

Tom: [01:09:07] Yeah.

Nigel: [01:09:07] So the question is, how does that dichotomy get bridged?

Tom: [01:09:11] Yeah.

Nigel: [01:09:12] And does the elastic band snap?

Tom: [01:09:15] And what happens if it snaps.

Nigel: [01:09:16] And what happens if it does, or do we put it together? I mean, one of the things, one of the dangers of the sort of bubble world of social media is that everyone, just everyone, everyone knows they're right. Whilst pursuing different realities. We have to find ways to have the conversations between people who hate each other. And that's hard, right? Because they don't necessarily even want to be in the same room. So that's the, that's the real challenge now is how to bridge those bridge those two tails. And we won't we won't emerge from Glasgow with one happy clappy tail where everyone agrees. But but my hope would be that we emerge with a with a realization that something really amazing has happened, that the promise of the Paris Agreement is being delivered.

Tom: [01:09:56] Do you agree that the only way that, in a way those two perspectives now can only be brought back together over time by the demonstration of action?

Nigel: [01:10:05] Yeah.

Tom: [01:10:06] This isn't about communicating it differently or anything like that, we have to show that we're really reducing and that will lead to a healing of that narrative or.

Nigel: [01:10:13] Well, I think fundamentally the healing will only come through action. I do think that sometimes the proclamations of victory are a bit too boosterish and a bit more humility and recognition. That that that the feeling of deja vu is justified. The New York Declaration is a really good example. I also think we need to do what you've just done and explain that this is now about systems transformation. So when one actor, like if corporates commit very difficult, but if governments and the value chain and civil society and finance are all committing you know we've talked about this like committing to the same exponential goals by 2030, then it starts to de-risk it for everybody and you get much bigger coalitions of the willing, which eventually create the momentum to be able to do it. But the proof of the pudding is still in the eating. But again, interestingly, when under Trump we had this big, we are still in movement of businesses, banks, universities, cities and states in America saying we are still in, although the federal government says we're out of Paris, we're still doing everything we can. That's what kept hope and momentum alive. And that's why, especially with the passing of the big infrastructure bill, you know, America is in much better shape now than it would have been if they had only been a federal government and that momentum hadn't continued. Similarly, in Brazil.

Fiona: [01:11:28] I actually remember listening to that during the COP and thinking being so glad that you asked Nigel these questions that were around in my brain as well.

Tom: [01:11:39] It's, I mean, I know we have lots of people listening, but it's always sort of weirdly a surprise when I discover anyone's actually listening to the podcast. But that's good to know you heard that one when it came out and so interesting to go back there to COP26, and we're actually now going to turn to more of a reflection on that pivotal moment. And I'm going to bring in now a good friend of mine who has been a close collaborator over the last couple of years, Charlie Ogilvie, who was the Director of Strategy for the Cabinet Office for COP26. He was right at the heart of government trying to work out how the country could pull the world together towards an ambitious outcome. It was very interesting to hear his recollection of how these tensions played out, and we caught up on the busy and noisy streets of London a couple of weeks ago.

Tom: [01:12:21] Something really interesting happened at COP26, where there was a moment that I remember, I wonder if you remember it in the same way, in the middle of the COP, where the announcements were coming, there was like this rolling thunder of like Finance Day and Energy Day and Forest Day. And the announcements were building up and building up. And then someone said, and I can't remember who, we're now on a trajectory to under two degrees. And the credibility line sort of snapped. And the activists who were both inside the conference centre and also outside, kind of stopped believing what was happening. And my observation is that from then on, the more commitments came, the less convinced the activists became. And to me, that sort of epitomized two sides of a almost philosophical debate. On the one side, there are all these pledges that were kind of full of optimism, and nobody knew if they could be delivered, but they were sort of saying, we're going to go to the moon inside ten years, let's do it. But then on the other side people said, you've lied to us before, and unless you're genuinely serious about meeting this objective and it's as it is, as clear and as as ambitious as the science demands, then you are selling out our future. And I'd just love to hear you talk about from within your perch of the Cabinet Office, how did you see those two sides and to what degree was it a problem and how could you use those two to your advantage in moving forward?

Charles: [01:13:47] The difficulty you have at this point in the in the movement is that there has been a history of targets that haven't been delivered at national level, at corporate level. And there's also clearly been actors who have felt that by making targets, they can get out of acting. So the integrity of the overall ecosystem is fairly weak. At the same time, there's a lot of people working both through the COP and through other organizations, like SBTi on trying to improve the integrity of the of the target setting and genuinely scrutinize what action is being taken by companies, countries, cities and regions etc. And this is constantly an equilibrium. And, you know, I think for those who are aware of quite how urgent this problem is, it can be extremely frustrating to see yet more targets when what you want to see is yet more action. But I also think it's dangerous to assume that somebody setting a target is necessarily trying to bamboozle you and greenwash, a desire for the status quo.

Tom: [01:14:52] And talk more about that, because that's the magic combination, isn't it? Is if we just sort of accept what everyone says as gospel truth, then we are opening ourselves to being lied to, which is not going to help anybody. At the same time, if we don't believe anybody, then it's so demoralizing for those who are trying to do good work. How do you get that? You know, how do you get that balance right?

Charles: [01:15:13] I mean, my my former civil servant self would say that there's a hugely important role for government and regulators ultimately in bringing this ecosystem into into focus, because, you know, there is a cynical but probably realistic view that there is you know, there's going to be a bit of the corporate space that's never going to do this for reasons for self, for reasons of of climate leadership. And will have to be made to do it. And therefore, you have to regulate, you know, the disclosure of their performance and what you think the right destination should be and push them down that road by government. And I absolutely think that you increase integrity in target setting by, through through regulated frameworks. We haven't got enough time, though, for us to wait for all the various organizations that globally have to pull their finger out to regulate this problem. So we need to we need to believe that some of this corporate momentum is real and we need to know how as a climate movement we can support that rather than just attack it. And that is a very difficult set of of distinctions to make. And as I mentioned before, there are lots of organizations, NGO organizations, organizations based in academia etc, and some led by groups of corporates themselves who are trying to create more integrity by the development of standards, by the scrutiny of actual development, actual delivery by companies and countries versus targets. But it will remain a very contested space for all the reasons that I've set out.

Tom: [01:16:53] Yeah. What, as you were somebody as Director of Strategy of COP26 sitting in the heart of government, what was your relationship like with the activist end of the climate movement and what do you wish it had been like?

Charles: [01:17:08] So we were very lucky in that I was given quite a broad freedom to second members of the NGO community into the team. And there were a number of a number of my team who I think probably considered themselves to be activists even when they were still working in government. So I was never short of a very frank view of what some of these commitments, how some of these commitments would be viewed.

Tom: [01:17:32] And could you have shared strategy with them? Like if you could you sort of call them up and say, oh, we've got a problem in the government of not not making this commitment. We need you to be on the streets kind of calling for change. Could you like collaborate behind the scenes?

Charles: [01:17:45] I think we there was a certain amount of strategy sharing that probably amounted to something that looked and felt a lot like what you say. But, you know, this is a community and there there has always been a good history of collective sort of strategy building. And people at different parts of it have different levers. And it did take us by surprise, I think, quite how much the integrity question around the targets became a focal point for the movement for the protesters. You know, there were lots of things for them to be angry at, at at COPs. There are still lots of people polluting and lots of people destroying rainforests and other ecosystems that are acting in very bad faith, not least all the other, you know, adjacent social issues that climate is exacerbated.