237: Our Story of Nature: From Rupture to Reconnection - Over to You

About this episode

This week, our hosts are rejoined by the incredible Isabel Cavelier Adarve. Tune in to hear them answer some of the brilliant questions listeners sent in following Christiana’s and Isa’s launch of their masterful recent mini-series, Our Story of Nature: From Rupture to Reconnection.

Christiana, Isabel, Tom and Paul muse on an intriguing range of questions from ‘how to teach citizens and governments about nature’ to ‘could bioliteracy transform things’? The hosts dive deep into philosophical questions about the role of religion, and more prosaic ones about supermarket food. They propose that it is possible, if we want, to sustain, and improve our relationships with nature wherever we are, whether in the heart of the city, or deep in the forest. Also, Tom tries to read out a question in Spanish and threatens to mastermind a presidential bid on behalf of Christiana!

NOTES AND RESOURCES

Isabel Cavelier Adarve, Co-Founder of Mundo Comun

LinkedIn | Twitter

Links to Our Story of Nature episodes:

Our Story of Nature - From Rupture to Reconnection - Episode 1

Our Story of Nature - From Rupture to Reconnection - Episode 2

Our Story of Nature - From Rupture to Reconnection - Episode 3

Our Story of Nature Intro Music - Catalina by Tru Genesis

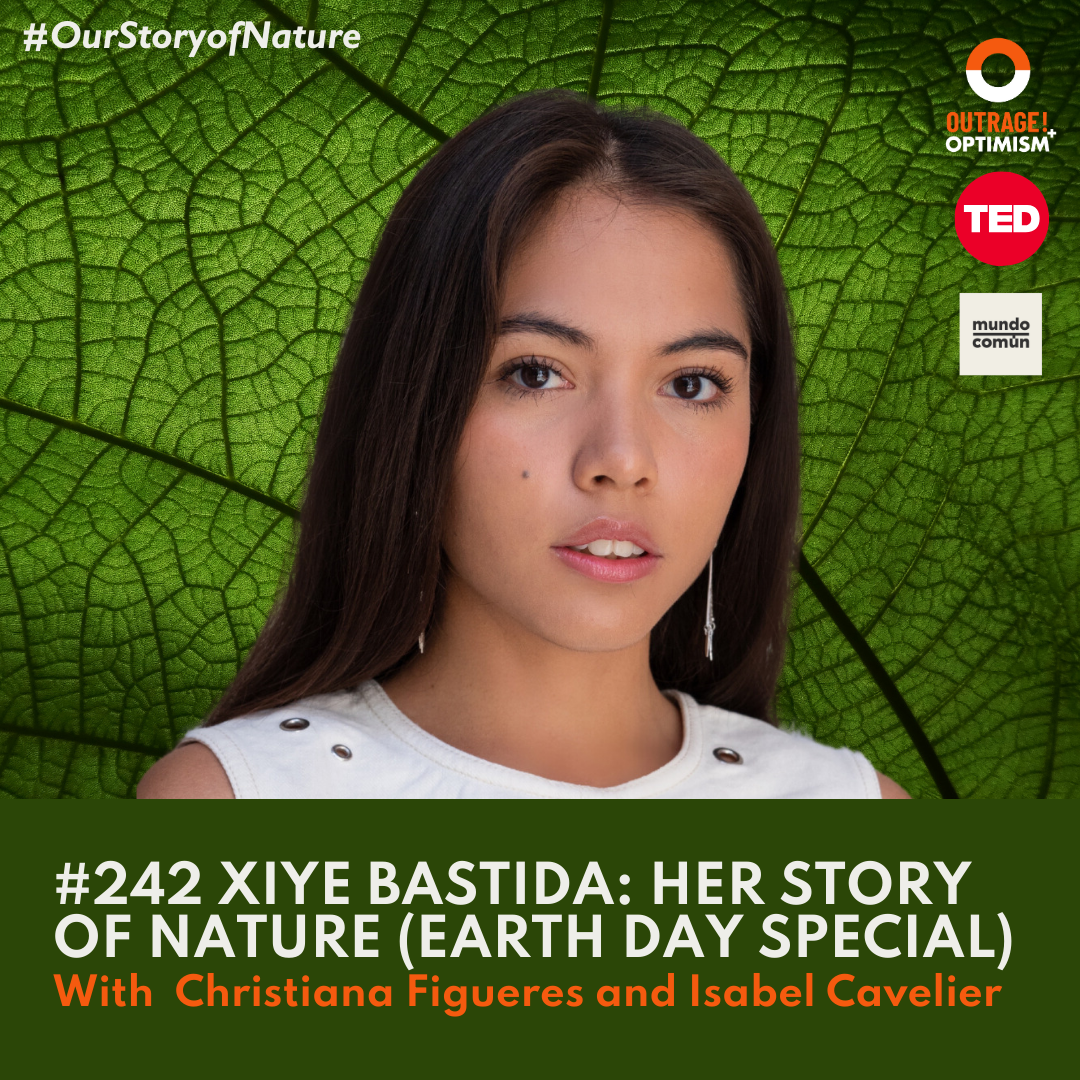

More on Xiye Bastida who features in the show.

Paul’s Book Recommendation - Small is Beautiful by E.F. Schumacher

The full, unedited interviews from the mini-series can be found HERE

Learn more about the Paris Agreement.

It’s official, we’re a TED Audio Collective Podcast - Proof!

Check out more podcasts from The TED Audio Collective

Please follow us on social media!

Twitter | Instagram | LinkedIn

Full Transcript

Transcript generated by AI. While we aim for accuracy, errors may still occur. Please refer to the episode’s audio for the definitive version

Tom: [00:00:12] Hello and welcome to Outrage + Optimism, I'm Tom Rivett-Carnac.

Christiana: [00:00:15] I'm Christiana Figueres.

Paul: [00:00:16] I'm Paul Dickinson.

Isabel: [00:00:18] And I am Isabel Cavelier.

Christiana: [00:00:19] Yay Isa.

Tom: [00:00:21] Welcome Isa. It's delightful to have you with us on the podcast. And today we are going to take your listener questions on the brilliant miniseries that Christiana and Isa put out a few weeks ago, Our Story of Nature. Thanks for being here. Okay, friends. So these are often my very favourite episodes of Outrage + Optimism, where we get to engage with the questions that you, the listener, have provided. And we got so many for this brilliant mini series, this came out a few weeks ago, it was a three part series that Christiana and Isa worked on together with a team for a long time, with many guests incredible voices. Clay did a beautiful job of providing the soundscape and the overall listening experience.

Christiana: [00:01:09] Indeed, indeed. Applause Clay, it was really beautiful.

Tom: [00:01:12] We are going to get into your questions. Clay is graciously receiving the applause, as you should. But first, Christiana and Isa, it's possible that some of our listeners may not yet have heard your mini series, and of course they should now go back and listen. But I wonder.

Paul: [00:01:28] Not yet had the pleasure.

Tom: [00:01:29] Not yet had the pleasure. But I wonder if you could just provide us with a few moments of introduction to what you did.

Christiana: [00:01:35] Isa, you go.

Isabel: [00:01:37] Okay, thank you Christiana. Well, it was a complete pleasure to do this mini series together. It was all about going through what was really the origin of the current crisis, what is, why deeply is it that we are finding ourselves in today's world in a climate crisis, in an ecological crisis, in a planetary crisis, you name it, beyond the, let's say, technical observation of it. We tried to go back in history and understand where was the root of the human understanding of ourselves as being disconnected from nature. And then how was the evolution throughout history to now understanding that we actually are nature. We have always been nature, and there is nothing, there's no space where you run away to and then try to reconnect to something else. We are that nature that we are trying so desperately to reconnect to. That was the original idea that came as we were together, Christiana and I just sharing stories and ideas on a very beautiful trip we did last year together basically. Load More

Christiana: [00:02:52] No, I was just going to say, one way of, that is what we do in that miniseries and one way of thinking about it, because we put it out in three parts. We had a long back and forth, back and forth how many parts is this going to be. Eventually we put it out in three parts, and one way of thinking about it is that we go way back into history, and we dig into those historical roots of our disconnection from nature, understanding that during that time we thought, or we had convinced ourselves that we had to live from nature with an extractive mentality, about our relationship with nature. And then we moved, and this is what we're experiencing now, to understanding that we actually can and should live with nature and stop the war on nature, if you will. But perhaps the most exciting is the third part of the series, where we look from the present into the future. And as Isabel says, we really realize that we are living as nature, that we can and should live in the understanding that we are inextricably bound, within nature. So it is quite a narrative arc. And honestly, if had it not been for our brilliant editors, Jenny and Shannon, we would never have been able to fit that whole long story into three parts.

Tom: [00:04:36] Beautiful, beautiful. So thank you very much for describing that. And it is an amazing mini series. And you say it's the future living as nature, but it's around now, right as well. I mean, I was reminded of William Gibson's quote, 'The future is already here - it's just unevenly distributed', right. It's emerging in these different pockets.

Christiana: [00:04:53] Exactly yeah, that's the exciting thing, it's emerging.

Tom: [00:04:55] It's the exciting thing. So, thank you. And now, let us dive in. So we have had far more questions than we're going to be able to get to today, but we're going to do our best and we're going to take them one at a time, in a format that will be familiar to long time listeners. And we're going to start with Isa. So, Isa, why don't you pick your question?

Isabel: [00:05:13] Sure, Tom. Thank you. I would love to start with Nicole Keller's question. She sent us her question in her own voice so let's listen to her first.

Nicole Keller: [00:05:26] Hi, my name is Nicole. I've been drinking in this series of episodes like a dry sponge taking up water. Thank you so much for it. I'm a greenhouse gas inventory manager, and I also practicing mindfulness meditation and training to become a meditation teacher. And I've been thinking about this topic of humans being part of nature for several years, and my mindfulness practice has really helped me feel this connection, this being nature in my bones. At the same time, I feel like many of those working in climate change at a bureaucratic level, policymakers and decision makers in governments and companies don't necessarily feel this connection in their bones. And I was thinking about this a lot at the last COP. We had thousands of negotiators arguing over various options in decision texts, there the conversation doesn't feel at all rooted in this understanding of connection to nature. In my experience, for those of us who didn't grow up with this understanding, it takes effort and determination to cultivate this connection. And given the scale and the urgency of the crisis we're facing, we need so many more people on board. How do we get people on board, enough people on board that aren't ready or willing to put in the effort it takes? Thank you so much.

Isabel: [00:06:52] Thank you so much for that, Nicole. I think that is one of the biggest questions that many of us are asking ourselves. How do we get enough people on board? How do we get these pockets you speak about Tom, become, ubiquitous or become momentous enough that it becomes a wave that is unstoppable? And I have to say that although there are no easy answers to that, one thing I can say is I was once one of those who had an experience of life that didn't bring this up front, and that went through the experience of finding myself so deep in this connection, I guess, or so longing for it, that I literally, decided that I needed to change my dedication, my life dedication, and do something else. One of the ways in which I think that, or at least that I feel that we, those of us who are feeling like this, could spread this out is definitely by trying to stop to try to be convincing others like preachers. I think sometimes this preaching attitude becomes very self-righteous. And I think the beauty, of spreading not only this narrative, but this way of inhabiting our earth is attractive per se. And the most important part is to do it yourself. Live yourself by it. And then as we invite others, it becomes, it's like a seduction, but less strong than this word. It's like others will be attracted by this, because beauty, I think, starts emerging when we most, many of us start living as nature. And so it's contagious. But I think it only can be contagious when we stop trying to preach and just trying to be incisively, you know, like incisively convincing. That's a part of an answer. I don't know if you all have other parts of the answer to this excellent question.

Tom: [00:09:08] I have a, I have something to add, but Christiana, you go first.

Christiana: [00:09:10] No, go ahead, go ahead.

Tom: [00:09:11] Well, I mean, the only thing I was going to add to Isa's great points is that, it's also really important to appreciate what is there. Like, we can think we're not connected and we need to reconnect. But often moments of connection come in little snippets. And if you slow down, you realize that you do have more connection and awareness and appreciation than you sometimes realize when you get caught up in thinking. So don't assume that there's nothing, because actually, sometimes it's just not consistent. And there's other things coming in too. We're very complicated. We do lots of things at the same time. We're disconnected. We're connected. We're full of thoughts. We're present. All of those things are true. And I think realizing that helps us realize we're closer than we think to where we want to go.

Christiana: [00:09:49] That actually is a really nice from both of you, is a really nice jumping off point to a question that I wanted to engage with from kolo gospodynm, I'm sorry if I am mispronouncing your name. And the question is, is it possible to introduce obligatory workshops on biodiversity for government members? So I have a couple, it would be fantastic is my first answer and at the same time, a couple of comments to that. First, to Isa's point about forcing people obligatory, maybe not, because, it might, we might have a backlash about that. So obligatory exposure to nature is perhaps not the best way. Second comment it's not just for government members. How about for citizens. So how would it be if starting certainly in your family, but at the very latest in school when you go to school, how would it be if we would all have bio literacy as a class and instead of sitting indoors, that we would go out and our eyes would be opened to the tree right in front of our school, or even the blades of grass or the little ant crawling on the blades of grass.

Christiana: [00:11:16] Honestly, you don't have to have a huge forest in front of you to begin to open up your eyes to nature. And, I just walked in, I'm traveling and I just walked into hotel like, just five minutes ago. And every time I walk into a hotel, I think like, is there anything living and green here. And usually there is one little plant somewhere and I go, and I really admire the beauty of each leaf of each of the, of each plant, even if it's just one plant. My point is, it's not about obligating anyone. It's about inviting everyone to open our eyes to that which surrounds us, from which we're actually not disconnected. And once we open our eyes to that, then every time there is more and more connection because we feel it deeper and deeper. So good idea to start with children from the time that they're small. But even if we didn't, it is never too late to appreciate that little blade of grass in front of your window.

Tom: [00:12:29] Isa, you want to come in?

Isabel: [00:12:29] Yes, I want, you made me think about something, Christiana. And it is that there's another component to that. And it is that sometimes we it's adjoining your both of your reactions, Tom and Christiana. Sometimes we feel we have to go and seek nature somewhere outside, somewhere else than where we are, even somewhere outside our own bodies. And actually as we, since we are nature, we can find nature in ourselves all of the time. Just breathe. That's it right. But I also wanted to compliment with one other point about this, obligatory or not, or let's say, how can we make people who haven't been so exposed to this come to this realization. And I think one of the things that I found attractive and that I think brings others along, although it may sound counterintuitive, is that the more one is willing to take the risk of staying with the discomfort of facing that connection with ourselves and with nature, and that requires quite a lot of courage. The more beauty you find, it's like you go deeper in the layers of beauty that are available to you the more you go out of your comfort zone. So I guess one thing that I would want, that one layer I would add is getting out of the comfort zone. And sometimes the comfort zone is, oh well, I go outside to nature to do my, you know, park trail every Saturday. Well, that's your comfort zone already. So how can you go deeper into your own nature. How can you be aware of your bacteria in your gut in a way that is very palpable, for example, and there are thousands of others examples. But I think that's an important component too. The courage of staying in the discomfort or the, or going out of the comfort zone.

Christiana: [00:14:24] Nice.

Paul: [00:14:25] And Tom on mute interestingly.

Christiana: [00:14:27] Tom, you're muted, but when you unmute one of you, Tom and Paul.

Tom: [00:14:31] Sorry, sorry element of verisimilitude. So Paul's going to come in but just before you do, so I had the great privilege of planting a whole bunch of seeds in my garden this weekend with one Paul Dickinson. I think it was either the first or the second time he'd ever planted seeds. I'm happy to report they've come up, Paul, actually this morning and, I was putting the seedlings out. I know, I know, I'll send you some pictures.

Christiana: [00:14:51] How did that happen, how was that so quick?

Paul: [00:14:51] Special powers, special powers.

Tom: [00:14:52] And I now planted some seeds in there this evening with my son. And we were planting these aubergine seeds and we were talking about nature. And you know how it's amazing. And spring is coming. And he was really getting into it. We had a great time. And then he looked at me and he said, can I go and play Minecraft now. And I'm just sort of reaching out to sort of also realise to listeners that this is bumpy and sometimes you connect and there are millions of people sitting in tech offices trying to persuade our children to sit in front of their screens. And that's not failure. That's okay too. You know, this is going to be both things. It's going to be both connection and those other things too and that's fine.

Christiana: [00:15:28] Absolutely, such a good point, such a good point.

Isabel: [00:15:31] Yes, excellent point.

Paul: [00:15:31] It's not beyond imagination that the screen could actually suggest you go out and plant some seeds.

Isabel: [00:15:36] It's happening, it's happening. I just heard from a colleague of mine who's in her early 20s that in the, in that generation, in that culture, there's something called rotting. I've been rotting, as in I've been on the screen all of the time, and that platforms already are suggesting you it's time to stop being on screen. Go out, raise your head, stop being on the screen, go out. And it is already embedded in the system.

Tom: [00:16:02] That is good. Although I would point out that there is no problem that more screens can't solve that problem by providing. Anyway, there's another thing, PD.

Isabel: [00:16:09] I agree.

Paul: [00:16:10] That was so badly explained Tom, but I think we all understood what you meant.

Tom: [00:16:14] You're used to that by now, surely on this podcast.

Christiana: [00:16:17] Paul, I so want to know your experience of planting seeds. It is so, so unusual for you. So I really want to know.

Paul: [00:16:27] I mean, the two things I remember was I got a little bit of stuff under my fingernails, and I spent quite a lot of time writing, in biro on ice cream sticks, what the seeds were. Because it would seem that once the seed goes in the earth, you actually don't know what it is, which is kind of strange.

Christiana: [00:16:39] No, you forget what it is. You hopefully you know what it is when you plant it, but you might forget it later on.

Paul: [00:16:44] It doesn't forget what it is. So why does it matter?

Christiana: [00:16:46] This is true.

Paul: [00:16:48] I'm just saying.

Tom: [00:16:50] It matters because you've got to know where to plant it. Keep them together. You know, these are big issues.

Paul: [00:16:54] I think you should just release the outcome. Okay, so I'm going to read out a question from, John Konrady. He says there's a spectrum of connectedness with people's engagement with the more than human. Some people feel deeply interconnected with life around them. Some don't trust anything that isn't wrapped in plastic. Nature is also positioned as a luxury. Do you see this moving in a similar way to sustainability, where it gets branded as a middle class premium? Or do we have more radical options to feeling part of the wider and wilder living world? Now, you may all have answers to this, but I wanted to, chip in that my own, even though I got some exposure to the countryside when I was growing up. I am a little bit of the only wrapped in plastic kind of world.

Christiana: [00:17:35] Oh, yes.

Paul: [00:17:36] I have friends who, you know, like to hang out with gigantic spiders, and I kind of don't think that's quite my thing.

Tom: [00:17:44] Paul, I think you should share your childhood vision of where you wanted to live when you were growing up.

Paul: [00:17:48] That's a little bit far fetched. I mean, shall we say that a world, a world further away from insects was one that comforted me when I was a child. I mean, I've got I think I've got like a DNA sort of fear of insects or whatever, but never mind that. I think that I wanted to come in on another angle, which is that, you know, nature is a global life support system. I understand global life support systems. You know, I'm not a surgeon, but I understand surgery, and the point is, I've been taught how this works, that there's this enormous machine called nature that is the life support system for this planet. And I have enormous reverence from it, for it. You know, whether I want to go swimming with sharks or maybe whether that's not quite my thing. And what I do know is that.

Christiana: [00:18:31] Wait, wait, wait, wait, Paul, so you have enormous reverence for it as long as it doesn't touch you, is that what I'm listening to? Is that what you're saying?

Paul: [00:18:38] What I'm driving at is that I want to kind of connect with people a little bit like me, who don't want to kind of, you know, wrestle with a polar bear, but still see.

Christiana: [00:18:47] Okay, fair enough.

Paul: [00:18:48] And one thing I think we all know is that a shop, especially like a supermarket, is a lie, right. That is not where food comes from. That's where you that's where you collect food in the city. And my final point would be just to.

Christiana: [00:19:00] Good job Paul, good job.

Paul: [00:19:01] Well, my final point would be to give great reverence to E.F. Schumacher, whose extraordinary book, Small is Beautiful, it's amazing. I mean, try and ignore the chapter on the coal running out, but everything else about that book is brilliant, and the point that he makes is that, because we live in cities, we are disconnected from nature. And we sit, you know, in city tower blocks making decisions about, you know, great forests and great oceans. And we have no feedback mechanism. And that is extremely dangerous. So what I'm trying to say, I suppose, is we can come at many different levels to that understanding, but come to it we must, thank you for the question.

Christiana: [00:19:38] I'll remind you of those words Paul.

Tom: [00:19:41] Yeah.

Christiana: [00:19:42] I'm glad that we're recording this because, you know, the next time you crouch in fear at the sight of an ant.

Paul: [00:19:51] Of you putting a giant spider down my back or something like, I mean.

Tom: [00:19:53] I think it's a great point, though, Paul, and I think that actually what you're what you've said is, you know, we're in a world where more than half of humanity is urban, where many people don't have direct connection to wild nature, such as we sort of imagine it or romanticize it in a certain way, and there can be a sort of homesickness that we have for nature some of us as we sort of remember that and think about it, but actually there has to be a way of addressing that in situ. It's not that everyone needs to abandon the cities and go out and find forests outside. And we've talked about sort of, you know, Christiana, you were talking about blades of grass or whatever else. Actually, one of the things I read a while ago is that nature provides being close to nature provides psychological benefits. And it doesn't matter whether that's a window box, a park near your house, or a massive manicured garden, or access to wild forests. That is a detail. Being close to those growing and living things is actually it's a holistic endeavor. And by that I mean it has the same qualities and principles at all levels of the system, whether it's small or large. And so actually, I think that you can get close to it by breathing. Every breath comes from the intersections. I mean, Stephan Harding, who was on this podcast a while ago, would give us a meditation where you would sit down and take breaths and realize that that is actually connected to all living things all around the world, it gets very close to Thich Nhat Hanh's thinking. So, yes, I think it's a really important point, Paul.

Isabel: [00:21:19] Well, we inhale plants exhalations, right. And they inhale our exhalations.

Tom: [00:21:27] Right.

Isabel: [00:21:27] So wherever you are, you are nature. And I guess that that division sounds a bit artificial, as if cities were not natural. Cities are the product of nature because we are nature. And as if cities were some sort of sort of, very how to say very clear thing that is like clearly divided from wilderness, but there is no such thing as a very clear, distinct frontier. Nowhere, not even in the biggest strips of urban, let's say, urban life in this earth, there is a strict border between urban and sort of quote unquote, natural, non-urban areas.

Christiana: [00:22:17] Especially if humans are walking down the street.

Isabel: [00:22:19] Well, exactly. So, but I appreciate your comment, Paul, because I think it's right. We may think, oh, I'm not that kind of nature person. I'm not so, you know, so outdoorsy. I love my plastic wrapping, but what you made me think is the other thing that we are realizing is we live in a mutant world. The Anthropocene is a biosphere where octopuses are working, are making pieces of art with plastic tools. This is happening in 2024. Our biosphere is already adapting, is already mutating. It's already fungi are learning how to metabolize plastic. I mean, how marvellous is that. And that's not to say we shouldn't worry. Obviously, there's a lot to worry about, but it's like, can we shift for a moment the perspective that there is something somewhere outside where you would go to then find some reconnection, or that there is some perfect future where there is no plastic, it's the way we are evolving and we need to do it in the more, let's say, caring way possible, I suppose in the way that can preserve life as a, as an ongoingness. I think that's the focus.

Tom: [00:23:44] All right. Love that. Okay, so I'm gonna hop in.

Christiana: [00:23:46] Tom, what question are you gonna pick up?

Tom: [00:23:48] Okay. All right. So, Johanna Köb, I'm convinced our fundamental gridlock at the moment is owed to implicitly expecting everyone's nervous system to react unanimously in survival mode. Its flighters going into ostrich mode, while fighters are throwing adult tantrums at those working on solutions and solvers desperately waiting for the cavalry everyone else to finally show up before they can move on. So if we take our variable nervous system response styles into account, how would we solve for that and design our way forward? So what I love about that question is, something that I have been thinking about for a while, which is everyone is needed and everyone is needed as themselves. And part of the orthodoxy of the climate movement at the moment is everyone trying to get everyone else to respond in the same way that they do. So people who are, you know, people will say, we all need to be really alarmed, and they're right. But sometimes we can fall into feeling like everyone else needs to respond in the same way as us. Or we can say, actually, you know, we need to take an optimistic and pragmatic approach, but then we try and get everyone to respond in the same way as us.

Tom: [00:24:57] But what this question is pointing to, and it's using the brilliant framing of a nervous system, and that there are responses that are intrinsic to people, is that all of those collective impulses are actually, when combined, part of the solution right. We need people who will wake us up and be alarmed and point to the problems and demonstrate that there's a real risk. We need people also who will respond to that stimulus with fight and with determination and say, we're actually going to we're not going to put up with this. We're going to be activists. We're going to be on the street. We're going to fight for change. And we need people who are going to quietly get on tinkering with more efficient batteries and the next solutions for electric cars. And the problem in our heads is that everyone who embodies each of those individual responses feels like it's only their response that will deliver the outcome we want. We've talked about this on this podcast before. We need a more inclusive and appreciative mindset so that we realize that each of those are needed, and collectively we get to where we need to go because each of them is insufficient on their own.

Christiana: [00:26:07] Nice Tom.

Paul: [00:26:09] Oh, yes.

Christiana: [00:26:10] Very nice.

Tom: [00:26:11] All right. I think we're back to Isa.

Christiana: [00:26:13] I think we're back to Isa.

Isabel: [00:26:15] All right. I'll take a very related question from Zaneta Sedilekova. I'm sorry if I pronounced that wrong. And this is the question, this way of approaching climate change or indeed biodiversity loss or wider planetary collapse is so important. My two cents to the discussion are that it is incumbent on those of us who are in the position to communicate about these to a wider audience, to learn how to communicate in a manner that does not trigger this response, or if it does, it guides them to process these intense emotions. As you say, none of the three responses of our sympathetic nervous system fight, flight, or freeze are helpful. They often lead to radicalisation between people and exhaustion of an individual. So my question for you is what are the communication methods we could employ with our audience to help them acknowledge the fear, embrace the pain, and feel the grief? And I feel you already probably gave a lot of the answer to this question in pointing, Tom, that we need probably many different modes of perception to approach this very complex, it's like a very thick present that we live in. That is a mix of all things happening all at once and all emotions happening all at once, and it's quite confusing. And I guess there is, as you were saying, value in fear, value in pain that is uncomfortable and that we will have to face and value in the grief that comes with the pain, and that, let's say, that pain from which the lotus, then the lotus then blossoms. But I also agree with the question in the sense that we do need to practice responses from our parasympathetic nervous system. It's almost like in times of great crisis or great urgency, great distress, how to practice, to go slow and be, in a serene state of being with our bodies.

Isabel: [00:28:24] Because I believe that one of the worst things and I think it is quite an epidemic. This is my diagnosis. It's an epidemic of our climate community around the world that we've been, so, let's say, permeated by the urgency and by the fear that this is such a huge unsurmountable thread. It's like a trans temporal hyper object climate change that we can't grasp it. And it's so full of anxiety that we exhaust ourselves and we're constantly in our sympathetic nervous system, but we never give a chance to our parasympathetic nervous system to actually restore ourselves. So I believe that to go to the question on how to communicate first, I think it's critical that we overcome the false dilemma between catastrophism and world saivism, or however you want to call it apocalipsis versus, you know, perfect world in the future. And we come back to the thickness of this present, and we acknowledge very explicitly and evidently that we live in a present that is full of paradox, where all of these emotions will appear. And I think the question is how we train to go through these emotions and to handle them collectively, collectively, because we've been, I think, used and trained to do this alone and to never talk about this. And I think that's what makes this worse. And that's what becomes the reason for exhaustion and radicalization and all of those things that you quote on the question, I'm not sure if others have more views on this.

Christiana: [00:30:07] Well, I was going to jump to another question because otherwise we won't get to all of them.

Tom: [00:30:13] Go for it Christiana, yeah.

Christiana: [00:30:15] So, I wanted to pick up Nadia's question and she says, you say we, but what do you mean by what this entails in practice, a collection of individuals consciously engaging in acts of imagination, something novel that emerges from new kinds of interactions between individuals, something else. I have my own ideas and experimental work, but I'm curious to hear your and others thoughts on this. So I love that question because it calls me to more responsible language. So thank you very much, Nadia. I really appreciate that. I will speak only for myself here, not for my colleagues who can then come in and say something completely different and contradictory. I notice, Nadia, that I use that word we very often, perhaps more often than I should. And I also notice, thanks to your question, that when I say we, I'm thinking obviously not just of myself, but I'm thinking of a collection, as you say, a collection of individuals that are basically agreeing with my view on X, y, z, and that I then take the attribution of saying we should do this or we do this, or we think that. And very often what I'm doing with that use of the word we is pointing in the direction of a thought or an action that I, in my judgment, think is beneficial for the common good. What I love about your question is that it makes me think about that, and especially it calls me to ask myself, am I thereby by the use of the word we, am I othering other people that don't agree with me, or that have a different way of thinking and acting.

Christiana: [00:32:43] And that is a really dangerous thing to do, to fall into the othering. But I want to say it is so easy for me to do it because of the way that I would love to see actions and thoughts move in a certain direction, which are, as I say, for the common good. But I really thank you that you have, I would say, called me out on the fact that when I say we and I'm thinking only of those not that I know, but many, many people that I don't know but who agree with me, then I say we and I speak as we and, I'm leaving others out. So thank you for that. Thank you for calling that out and making us aware of the fact that, as Tom was saying, we actually need all these different ways of acting, all these different ways of seeing, in order to be able to deal with the diversity that we have, the bio and human diversity that we have on this planet. So thank you, Nadia, for a little lesson embedded in your question.

Tom: [00:34:10] Although I have to say, I mean, it's almost like, you know, if I didn't know you, then what I would say is that you instinctively build your authority by kind of representing a group of people. And so given that fact, I'm going to also pose a second question to you, which everyone is going to have to excuse me okay, but por favor postelese como Presidenta por favor.

Paul: [00:34:36] Big oui, big oui.

Tom: [00:34:37] That question is from, Valueria Aguiluz and someone's going to have to correct my pronunciation.

Christiana: [00:34:43] Aguiluz

Tom: [00:34:44] Aguiluz. And it means Christiana, please run for president. Costa Rica needs you. You're demonstrating your consensus building ability. You talk about we.

Paul: [00:34:56] She's nodding, I think she could do it.

Tom: [00:34:57] You could be on the floor of the UN saying, we will change the world in this way. And you could represent your beautiful country. I know you're keen. Come on.

Paul: [00:35:05] Listeners, I was lying, she wasn't nodding.

Christiana: [00:35:07] No way, no way. Thank you for the thought. I appreciate the sentiment and I'm quite happy doing what I'm doing.

Tom: [00:35:16] Next time you stay at my house, I'm going to steal your phone and tweet you into politics. No, I'm only joking, of course I'm not.

Christiana: [00:35:21] I'm never going to come back to your house again, Tom.

Paul: [00:35:25] It's kind of like you can't become president under protest, can you, like, you can't be, like done to you.

Tom: [00:35:30] Also my Spanish isn't good enough. People would notice immediately, yeah. PD.

Paul: [00:35:36] Okay, let me come in with a question from Valeria Amezcua. She says, whatever, however, I've butchered her name, in this beautiful set of three series you reminded us of the book The Ministry of the Future, but I was left intrigued. Belief is such a powerful tool humanity has used to get things done, but every day more people become atheists or agnostic. And she says, I am. So how to reconcile the spiritual part to help solve the 21st century problem. And so I think I'd love to hear us all answer this perhaps, but I personally am an atheist, and I also but I also see genuine genius in spirituality and especially, I would say, Buddhism, which I've learned something about, not least through you Christiana. Religious approaches, shall we say, like reverence for something bigger than ourselves, I think is a really important part of what I would call right relationship with the universe. And it can provide kind of great relief, to the impossibility of existence in some regards. This, me we thing. I mean, you all on this podcast, no little me, but I've also sometimes been big me and when I'm big me, I'm almost always crying with joy because I'm part of something extraordinary and sort of world changing. I think the worst belief.

Christiana: [00:36:59] Who's the big me Paul, what is big me?

Tom: [00:37:01] The Paul Dickinson.

Paul: [00:37:03] Well, I'll give you an example, when every single country in the world spontaneously backed a climate change accord in Paris in 2015, I was sort of sitting there and I felt something, and it was important, and it was good. I can think of other examples.

Tom: [00:37:21] Don't you remember he refused to come to the party because he was sitting there on the front row listening to, like, all of the countries stand up and give their half an hour speech.

Paul: [00:37:28] Russia, this is great, Saudi Arabia, this is great.

Tom: [00:37:29] And I hope I'm not exposing you too much, Paul, with tears streaming down his face.

Paul: [00:37:33] Yeah, I did have tears streaming down my.

Christiana: [00:37:35] You did, you did.

Tom: [00:37:35] As countries talked about what they were going to do and how they're going to get on top of this.

Paul: [00:37:39] That's big me.

Christiana: [00:37:42] That's big you.

Paul: [00:37:42] And I'll jump in front of any bullet heading for that. You know, the worst hell is belief that all meaning ends at the fingertips you know, we live in natural human systems. It was Gregory Bateson, I'll leave the last word of my answer to him. This sort of thinker who a little bit of film of him on a panel saying, I have sometimes caught myself sometimes thinking that something was separate to something else. And a very foolish thought, I think, was his implication. Because they ain't.

Christiana: [00:38:12] They ain't.

Isabel: [00:38:14] I think next, was it Tom?

Tom: [00:38:15] Yeah. I'm going to hop in, just quickly before I do, you suddenly, I remembered Paul and, editors may or may not choose to leave this in, but when I first met you in 2007, and I was meeting lots of people involved in climate, and there's, I mean, I'm sure other hosts may not realize this, but a lot of egos sometimes in the climate movement. And you probably don't remember.

Christiana: [00:38:37] No way. No no no no way, really.

Tom: [00:38:40] You met my beloved wife, Paul for the first time in 2008, Natasha. And she said, I've never met anyone who is so motivated by the sadness of what we might lose, and I hadn't realized it about you. And then I was like, oh my God, that's true. He actually has this motivating factor, even though you're scared of spiders and other things like that.

Paul: [00:39:01] We all do but I had the good luck to speak to your wonderful Natasha, who found that in me so credit to her eyes.

Christiana: [00:39:11] Very sweet, love that.

Tom: [00:39:12] Credit to you, credit to you as well. Right okay, I think I'm up. So I'm going to ask a question by Inna Chilik. And this question is, nature's balanced ecosystems thrive because of interspecies collaboration for the benefit of the whole, not just a singular species. Can we reshape our human structures and institutions to mimic that interconnection and interdependence? How would our society look? So, I mean, this is a fascinating question because it speaks to the thing that I think lights everybody up when they think about a future, that we've really done this, a regenerative future, if you think about it, you know, all respect to, you know, transformed energy systems and grids and batteries and we need those and they're really important. But the thing that gets everybody lit up is the idea that the forests come back and the insects come back, sorry, Paul, and the birds and the animals. And actually we see.

Paul: [00:40:07] I love the insects, I love them.

Tom: [00:40:09] We see a world in which we are participants in a much larger whole. And I think the idea of co-creating the planet is kind of slightly beyond my ability to imagine with other species, although I can understand that that's a place we might get to. But the the other feature of natural systems that I think we have let go of in our Cartesian blindness is the concept of emergence, and the fact that we have almost no control over what the outcome is. And you need to behave in accordance with what's appropriate within your role of the system. And then an emergent property appears from those series of interconnections. So that's a place that I try and live from a bit more actually these days. And to let go a bit and the world loses both its threat and its promise when you live like that, because you realize you don't have control. So all you can do is the next right thing according to how you see your role in that web of interconnections and the emergence has to come. And it can be small, it can be in your area, or it can be enormous and systemic, as has been the case for many people. And that, of course, we hope for. But that's not the thing. The thing is the engagement and the emergence takes care of itself. And I think if we can understand that a bit more, that also helps us appreciate the concept of agency that we struggle with so much.

Christiana: [00:41:31] Yes.

Tom: [00:41:32] Does that answer make any sense at all?

Christiana: [00:41:34] Wonderful. Yes it did a lot, a lot of sense. Could I ask Isabel to answer the question that we got as a voicemail from Aurora Brown, because it refers to a two year old child, and Isabel has a young child.

Isabel: [00:41:52] Of course.

Tom: [00:41:53] Nice.

Aurora Brown: [00:41:55] Hello Christiana, Paul and Tom. My name is Aurora and I live in the beautiful Cape Town, South Africa. Now, before I ask my question, I just want to take a moment to thank you from the bottom of my heart for all your work, which educates and inspires me. There is so much justifiable outrage in all the climate content I consume, but after listening to your podcast, I always feel more optimistic and energised to take action for the future. I also want to give a shout out to producer Clay, his friendly, inclusive and generous button at the end of each episode really makes me feel like I'm part of your community. Now for my question to Christiana and Isabel about their fantastic, thought provoking series. I have a two year old child in my household who is still a relatively blank slate, who hasn't yet absorbed the trappings of capitalism and patriarchy, but who is inheriting a fragile future. So my question is, what is your advice for raising a child to live from, with, and as nature, while also ingraining a sense of optimism in them for their hopefully long life on the planet? Thank you once again and sending you all lots of love.

Isabel: [00:43:18] All right. Aurora, thank you so much for this beautiful question. I have a five and a half year old, and, I share your question in a very deep way, and I don't have the right answer, but I'm sure, like you and so many other mothers and fathers in the world and people caring for little younger humans are asking, we are asking ourselves how to do what you're asking to do. How can we give them a sense of agency right, and how can we bring them up or maybe take their hands as they grow up, with a deep connection or understanding, being aware of their own connection. And I suppose there, at least what I can tell you from my own experience is I, what I do is I, I do try to be very explicit and very intentional about how we nurture our own dialogue with other than human beings together. And I can tell you an anecdote of last night. Last night, our district, they were this, they have decided to chop down a beautiful, massive tree, a centenary tree that lives right in front of us. We pass by this tree every single day.

Isabel: [00:44:44] And, they were just putting it down because it was, a risk to, you know, to the street where it's planted or something like that. And so my daughter and I, we decided to go and not just we tried to, you know, send a letter and, speak to the neighbours, etc. but we also went to keep the tree company, and I think she will always remember, and I will always remember that she and I went that night to that tree to give her love to just hug her, to make her beautiful. We just wrapped her in all sorts of beautiful coloured threads, and we gave her as a present or as an offering several drawings that my daughter did and some words that I wrote. And we prayed with her and we said, if this is your time to, you know, to just turn into something else, let it be peaceful and let you feel that there are other beings on this earth that are keeping you company, even if we cannot stop that she was going to be completely dead in a few days. So that is one little example, that I can give from my experience that I try with my young daughter, with her I connect together with her, with other beings in ways that make it clear that we are the same as others. When we are eating, I tell her, give thanks to this being that is offering their life for you to be nourished because you're becoming that being that you are eating. If it's a tomato, you are becoming that tomato and that tomato is becoming you. So I'm very intentional about it, I must say I'm still quite anxious about how to communicate about the climate crisis with her. I've started telling her, but I also give her hope that this is the work of our time, that this is why we have to nurture caring relationships, and that it is going to take my entire life and her entire life. But that is precisely what we are here for. So a bit of a long answer. Thank you. But you triggered something very live alive in me today really. On actually on, forests day, International Day of Forests, 21st of March. So a beautiful anecdote for an important day to remember trees and their beauty.

Christiana: [00:47:19] Very beautiful story.

Tom: [00:47:20] What a lovely answer, thank you.

Christiana: [00:47:21] Yes beautiful, thank you Isa for sharing that very beautiful. And that actually brings me to, I think, a related question.

Tom: [00:47:30] I have just one comment to add to Isa's piece before we move on, if that's all right.

Christiana: [00:47:33] Oh I'm sorry, go ahead.

Tom: [00:47:33] Yeah, no, no, it's fine. So I have older children, they're 10 and 12, and, I mean, not that much older, but they're still children, but they're older. And I would say a couple of things to Isa's beautiful explanation. And the first is that the world will get in. The world is a complicated and noisy place, and you can't grow, you can't raise your children in isolation from that, and that will be a bit painful. And that will involve all of the things that you're struggling with about the world around capitalism and separation and technology and other things like that. And that doesn't mean you're failing as a parent. It just means that it's complicated to grow up and that actually they need those things as well as part of the world. The education system is fundamentally a product of our capitalistic system. And my God, it's painful to watch young people go through it. And I would say it's important to sort of sit with them and sympathize with them, that that's painful, but also to not set the bar too high in terms of I mean, when I had young kids, I was like, well, I'll raise them in separation from this and I'll be able to like, instil some other kind of values. And as they get older, you kind of realize you're part of the world and you're intrinsically and fundamentally connected, and you can impart your values and you can help them understand, but they're also going to have to live their lives in this complicated, noisy, messy world. They're going to get addicted to screens. I mean, this may be too defeatist for some people, but I would say there's a degree to which the world is going to get in and accepting that, sort of frees you up a bit as well, that it's hard to sort of be too perfectionist about it. Paul's laughing at me.

Paul: [00:49:10] They're going to get addicted to screens. Nothing is, what is it, nothing is impossible Christiana always tells us, like it is possible that there are children all over the world that are not addicted to screens.

Tom: [00:49:20] That is true, but what I mean is, screens are an ever present element of their generation, and they will either be associated with them or they will be associated with them by an absence. So you I know some people who say I'm not going to let my kids look at screens. This may be a small rabbit hole, and those kids have an absolute burning desire to do the things that their peers are doing, because that's part of what this generation is. So I just don't want people to feel like they're failing when they don't, when they aren't able to meet this bar of connection every day with their kids because of course we all want that. But raising kids is hard. Christiana, we're being told to get on with it. Go for it.

Paul: [00:50:00] We're going to give the last question to Christiana, but I'm still unconvinced by associated with an absence. Right, Christiana.

Christiana: [00:50:06] How are we doing on time? Do we have time for one more question?

Tom: [00:50:10] Yeah. Last one.

Paul: [00:50:10] We have time for one more.

Christiana: [00:50:12] Oh, no. Okay. Pressure, pressure. The pressure is on. Well, I'm going to choose the question from Corinna Cunningham because it's very related to what Isa and Tom have just shared. And Corinna's question is, feeling the grief is scary. And I think people avoid it because we as a society have not been taught to properly experience it. If we have the tools and education we could and then perhaps progress. So this is quite, quite close to Isabel's beautiful story of, feeling the grief of a tree that is going to be cut down, and I would go even farther than that Corinna, I would say even befriending death, I, had the incredible opportunity last year because of the death of my sister to intentionally and very deeply become in my head and in my heart and in my body, very close to death, and to understand that death is a part of life, and that joy is adjacent to grief, and that happiness is adjacent to sadness. And to understand that all of this actually is part of each other. It is a cycle that we go through constantly, and as you say, if we understood that and if we didn't turn our backs on grief and pain and death, the death that we're seeing in ecosystems, the grief that we feel about those ecosystems being harmed, the fear of what is the future that our children and grandchildren will be experiencing if we actually have the courage to face that head on, embrace it, understand that that is part of our life as Tom was saying, this is part of our life. Then we can actually, if you will, metabolize those emotions and find that they can be routes to many other different emotions, such as the determination to put up a good fight, such as love for trees, for humanity, for everything that is disappearing and hence from that love find the capacity and the tenacity to continue to work for the cycle of life, not for life alone, but for the cycle of life, for the full cycle of life, for the full web of life that includes life and death and sadness and happiness and to really be able to understand, wow, we are we we have as many emotions as a rainforest has species in it, and how beautiful that that is the way that we are made and how beautiful that everything that we're made of and that we perceive through our five senses actually brings forward that richness of emotions. And not to think that we can only experience joy and happiness and birth and life, but rather to open ourselves up for the full cycle of emotions and live life deeper and fuller, and perhaps in more reverence and in more awe of everything that is around us and inside of us. Somewhat philosophical answer, sorry about that.

Paul: [00:54:46] It's beautiful.

Tom: [00:54:48] It's a beautiful answer, I love that, thank you.

Isabel: [00:54:49] It is beautiful. Thank you Christiana.

Tom: [00:54:52] I don't know if this is a male female thing, but I have to say, I don't think I have as many emotions as a species in a rainforest, but maybe I don't have such a rich emotional.

Christiana: [00:54:58] Oh yes you do Tom, I've seen them.

Tom: [00:55:02] Isa, I think you wanted to come in.

Isabel: [00:55:04] Yes, just very quickly, Christiana, because you've reminded me something I have been meaning to say since we recorded our mini series, that, by the way, I invite listeners to go back and listen to if you haven't done so yet. And it is that there are some griefs in this world that are truly unspeakable pains, and many of them are occurring right now. And I think that we do want to make space from the love that you are mentioning, Christiana, to hold that unspeakable pain, the pain of a mother.

Christiana: [00:55:41] Totally.

Isabel: [00:55:42] With her child, you know, dying in her arms in Gaza or of the Ukrainian children or the Yemenis or the Colombian internally displaced and etc, I mean, you know, I don't want to make this a list of, grievances. But I do want to say explicitly that when we speak about grief and the importance of befriending pain and of being able to being reborn from that pain that does not underestimate or even try to slightly understand the un-speakability of those pains that we are currently seeing in the world. And I want to make sure that we are clearly holding those pains with us.

Christiana: [00:56:34] Yes, very good point, thank you. Yes, absolutely.

Isabel: [00:56:38] It's not minor. And I wanted to be explicit.

Christiana: [00:56:42] Yes, good good good good. Very good, thank you.

Tom: [00:56:46] Thank you.

Christiana: [00:56:46] Thank you so much, everyone. Unfortunately, we have to come to a close and we didn't get to all questions, so I'm very sorry about that. But as Isa says, go back and listen to the mini series if you haven't yet. And do continue to write to us because we will read. A couple of things here. First, that, thanks to Isabel and her wonderful team at Mundo Comun, they are working on a Spanish version of this mini series that will be a little bit similar, but quite different.

Isabel: [00:57:26] But not, yes.

Christiana: [00:57:28] Maybe not, maybe yes. But that will be, that is in the works. So we can look forward to that. Also, I'm asked by the team to let you know that, we had so many absolutely fantastic, brilliant interviews with the people who participated as guests in our mini series, and we can actually offer the unedited, full version interviews with all of those people on our website. Quite, quite a treasure trove.

Tom: [00:58:02] And we might drop some into the feed, right, I mean, there were some amazing people in there, so we might drop some into the feed, yeah, great.

Christiana: [00:58:07] Amazing, amazing.

Isabel: [00:58:08] So many amazing interviews, yes.

Christiana: [00:58:09] Yes, so quite a treasure trove there for you all to dive into. And finally, thanks so much to the listeners who have listened to this series, to those who sent questions and for those who will listen. And what better way to finish up here than with a clip from our good friend Xiye Bastida, who is just such a ray of light, and such a profound thinker, especially because she's so young. She really is an old, old soul in a young body.

Tom: [00:58:50] And Clay will answer one more question in his normal credits at the end so stay tuned for that. All right.

Christiana: [00:58:54] Oh yes, Clay.

Clay: [00:58:54] Stay tuned.

Isabel: [00:58:56] Thank you.

Tom: [00:58:57] Thanks everyone, thanks Isa, bye everyone.

Paul: [00:59:00] Thank you, bye bye.

Isabel: [00:59:00] Thank you all. Bye bye.

Sarah: [00:59:01] Thank you, sorry.

Tom: [00:59:05] That was Sarah Thomas everybody, the producer of the podcast. No one knows why she said thank you, but welcome Sarah to the podcast.

Sarah: [00:59:14] Having my five minutes of fame.

Clay: [00:59:21] So there you go another episode, Outrage + Optimism. I'm Clay, thank you for listening to our podcast. I will end the episode with Xiye in our true to form nature series style, as promised in just a moment, but I want to get the credits out of the way so we can do that. So a few things to bring to your attention. Sarah and I literally just hit publish on the Our Story of Nature series deep dive page, where you can listen to those standalone interviews that were mentioned earlier, outrageandoptimism.org/nature-deepdive-series. Don't remember that, you can just click the link below. Super easy. We hope you enjoy that. A massive thank you this week to Isa for joining us on our Q&A. As always with our guests, you can go to the show notes below. You can connect with Isa and you can find out more about the work of Mundo Comun. Check it out. And of course, this week we had many special guests, all of the listeners who submitted questions. It made this episode possible. So thank you from all of us and apologies if we didn't get to your question. We do these often, so we're really looking forward to hearing what's on your mind for the next one. Best way to find out ahead of time, listen to our podcast, hit subscribe or you can follow us on Instagram, LinkedIn and Twitter, X I don't know. Okay, last but certainly not least, we received a question from Jonathan Smith, that I will be taking right now.

Clay: [01:01:00] And the question reads absolutely fantastic series, great co-hosts with real insight and energy. One question what is the intro music? It's really good. Okay, a curious ear has reached out. I'm happy to share. The song is Catalina by Tru Genesis. You can check the, here, let me actually just play it. Okay, here it is. You can check the show notes for a link to listen to it on YouTube. I actually picked this one because after skimming through like a few dozen songs, when this one came on, I kind of imagined Christiana and Isa putting on these, like, cowboy hats and jumping on their horses and, yeah, just like riding off into the sunset to solve this, you know, climate change mystery or something. Anyway, it made enough of an impression on me. I really liked it. Jenny, Shannon, Sarah they all liked it, so it made the series. Thank you, Jonathan for the question. Hope you enjoyed the song again link in the show notes. Okay, let's slow down here. Let me turn this off. Let's take a deep breath. So let's end our podcast in true our story of nature style with Xiye Bastida. Let's bring in a little ocean here. You can take a seat, get comfortable, settle in and listen. Xiye will take us from here. Enjoy your weekend. We'll see you back here next week.

Xiye Bastida : [01:02:54] It is so easy in the climate movement to fuel our fight from resentment, to fuel our fight, from rage, to fuel our fight, from, you know, a feeling of disappointment for what the world is today, especially for younger generations. But I know that that cannot fuel my fight, because then that's the world I'm going to create, one that has those characteristics of my thoughts. So I choose to be optimistic. And ever since I first met you, I think four years ago, and you talked about stubborn optimism, I haven't let that go. And it has informed every single step of my activism that I need to be optimistic, because only then will the world be what I want it to be, which is safe for my children, free of violence, connected with nature. And so my homework for myself every day is to think and walk in the best way that I can, so that I can head to that future that I'm proud of for my kids and my lineage.

Isabel: [01:04:03] So you got us both crying now.

Christiana: [01:04:05] Yeah.

Your hosts

Christiana Figueres

Follow Christiana Figueres on Instagram

Follow Christiana Figueres on Instagram

Tom Rivett-Carnac

Follow Tom Rivett-Carnac on Instagram

Follow Tom Rivett-Carnac on Instagram

Paul Dickinson